Editor's note: This column was written by NBC Sports Bay Area columnist Monte Poole.

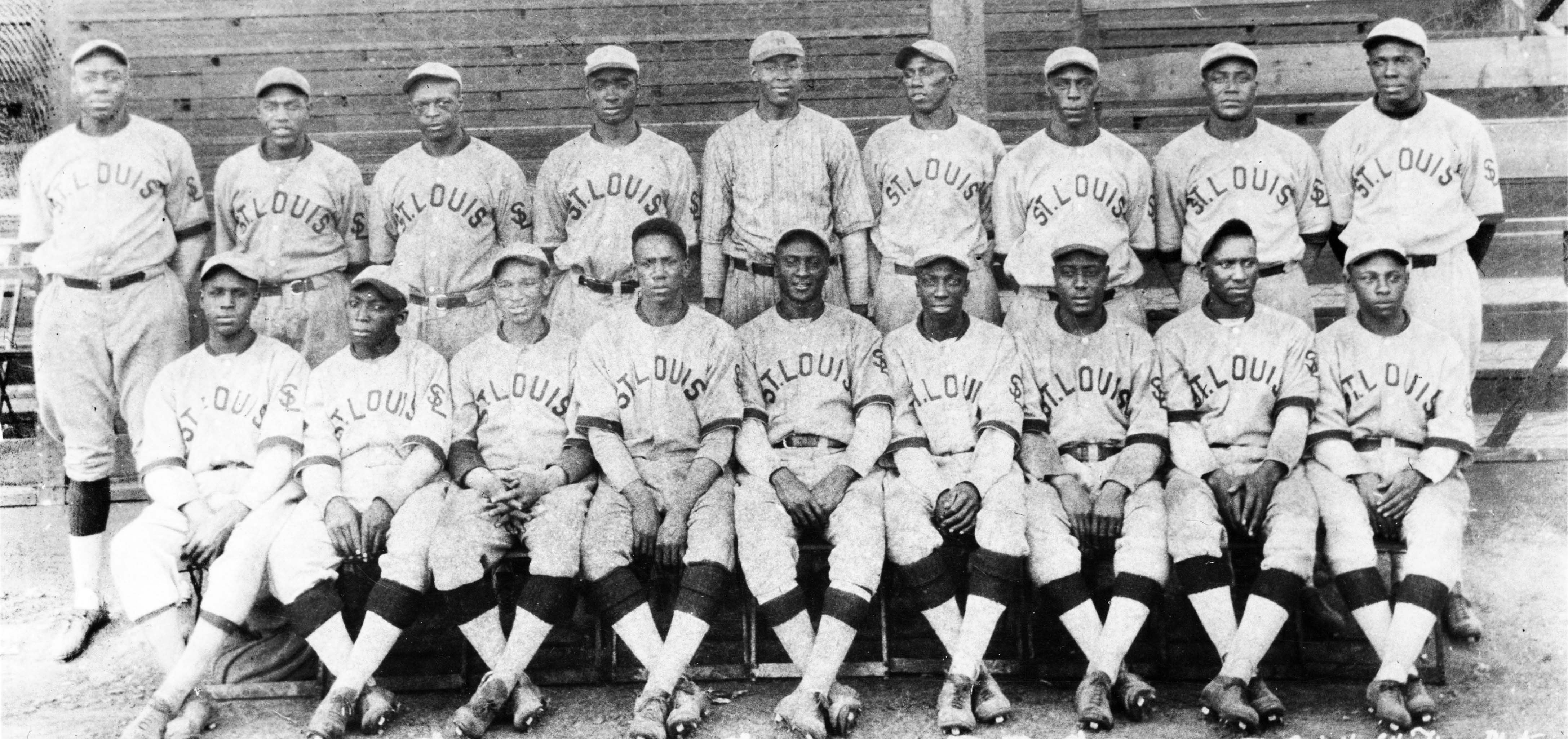

No matter the decisions made by the almighties of Major League Baseball, Negro Leagues Baseball always will be separate. It was a product of Black athletes and executives creating a league apart largely because they were barred from MLB. NLB was the only route to professional baseball in America.

That much is etched on the walls of our nation’s inglorious history. It is as separate in 2024 as it was in 1964 or 1904. To paraphrase, segregation forever.

Unable to expunge the “separate,” MLB on Wednesday officially embraced the other element of the doctrine made infamous in 1896. It will consider records and statistics compiled in the seven NLB leagues as “equal.”

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

Which brings joy to many, including the descendants of those who participated in NLB and surely Bob Kendrick, the president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

“You can say that it's been decades in the making,” Kendrick told NBC Sports California's Brodie Brazil and Bip Roberts on Wednesday. “But when we talk about it from an official capacity, we go back to December of 2020, when Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred made the historic announcement, first and foremost, that Major League Baseball was finally recognizing the Negro League certainly for what I've always known it to be: a Major League. And that Major League Baseball would roll in the statistics of the Negro Leagues into the record books of Major League Baseball.

“That truly was a historic moment. From that time on, a dream team of Negro League historians, researchers and educators started the daunting task of unearthing this data to put it in a quantifiable fashion. Which got us to this point when it was officially released today.”

A committee of 16 men and women, including six-time All-Star and Vallejo native CC Sabathia, comprised the statistical review committee. After more than a century of marginalization, the gates are open. Seems considering the quality of play in NLB, which from 1900-1948, according to official records, posted a 316-283 record when facing whites-only big leaguers.

Statistic apartheid is abolished, with leaderboards being rearranged to accommodate the statistics of more than 2,300 NLB players.

This can only be enlightening for fans previously unaware of the quality of play in NLB – and perhaps wholly unfamiliar with the those who longed to enter MLB but were denied based on skin color.

Like, for example, Josh Gibson. True fans know the name, but others will be introduced. Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972, his .372 batting average displaces Hall of Famer Ty Cobb (.367) atop the career batting list. Gibson is among five NLB players now among the top 10 career batting leaders.

Gibson’s assault on the record books amount to a takeover inasmuch as he is the career leader in slugging (.718) and OPS (1.177), while also the single-season leader in batting average (.446), slugging (.974) and OPS (1.474). Observers argue, convincingly, that Gibson, who died of a stroke at age 35, was superior to Jackie Robinson and, moreover, the best hitter who ever lived.

The pioneer Toni Stone, already the subject of stage plays and multiple books, is elevated. The woman paid her dues in NLB before spending her post-career years in Oakland before dying in 1996, becomes the first of several females to claim official MLB statistics.

It’s notable that MLB began moving toward this in 2020.

“We were in the throes of a worldwide pandemic,” Kendrick said. “We had all witnessed the murder of George Floyd. We were on this social movement thrust. The Negro League Baseball Museum was being finally recognized for what it really is, and that is one of the nation’s preeminent social justice civil rights institutions.

“And I do think that commissioner Manfred seized the moment, understanding that this is one way in which baseball could support this movement and in its own way and to recognize the Negro Leagues and the fashion in which it did.”

The killing of Floyd in Minneapolis galvanized millions in America and beyond. It revived efforts to address all manner of inequality and human rights. In the wake of that, the phrase “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” was uttered in corporate hallways throughout the country.

It was a concept that, recognizing the biases of the past, would genuinely commit to equal opportunity and mobility for races, genders and ethnicities previously disenfranchised.

When the movement receded, backlashers pounced and started trimming many DEI programs into oblivion, if not eliminating them altogether. The phrase DEI is, for many, one of the most detested acronyms in the lexicon.

Yet MLB, with its paltry representation of Black Americans on the field and in the boardroom, followed through with a commitment. Belated inclusion is all that is available to those of NLB.

Saluting the past doesn’t address the very real issues of MLB today. But this decision can be appreciated by those connected to NLB, those who follow sports and believe in a proverbial level playing field.