Bernie Sanders has spent much of his career on the political margins, an outsider looking in.

Now, the protest politician is learning what it’s like to be the front-runner for a major political party.

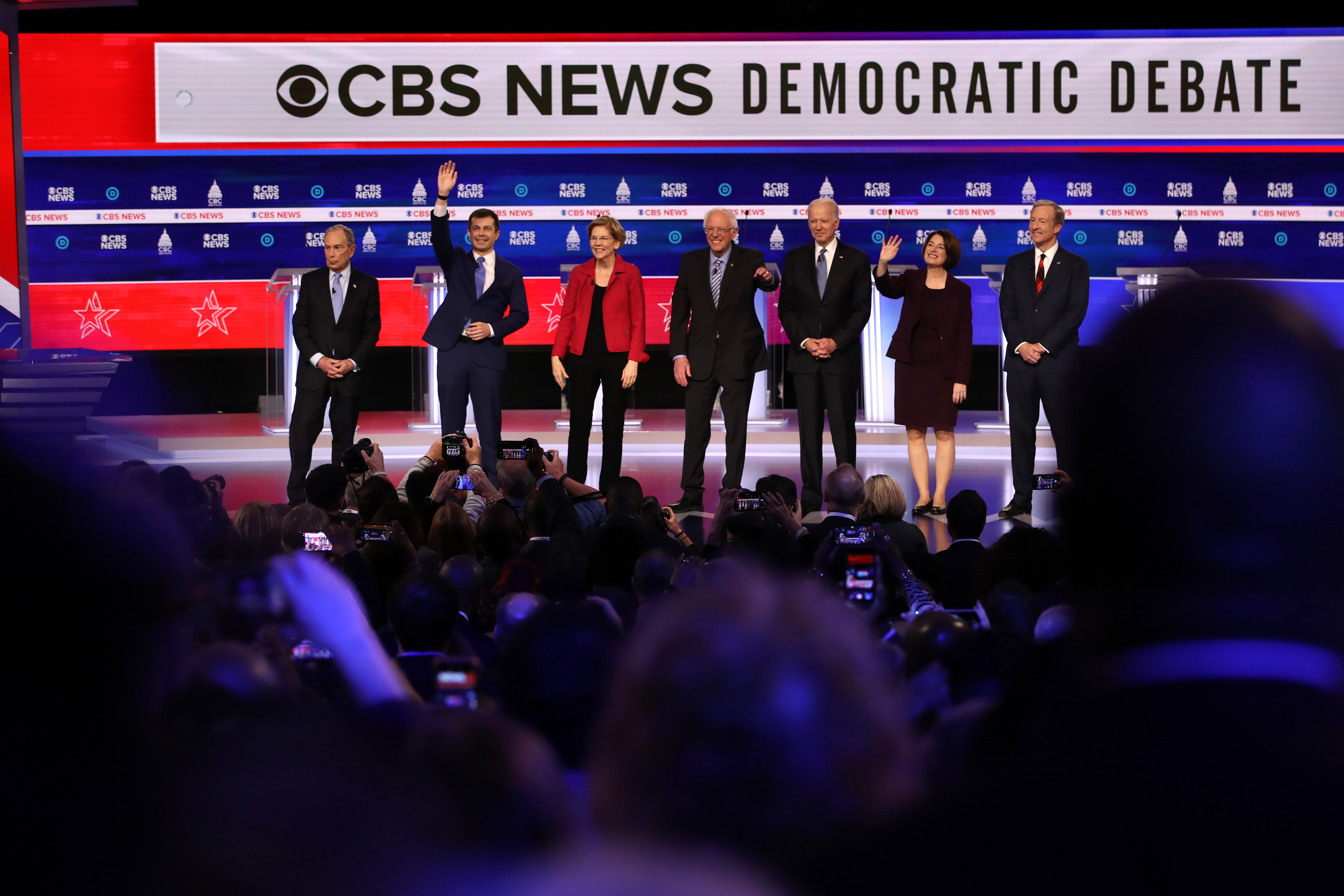

Sanders was the target of persistent attacks in Tuesday’s Democratic presidential debate, both from his more moderate rivals and the competitor closest to him philosophically, Sen. Elizabeth Warren. He faced granular questions about the cost and scope of his sweeping domestic policy agenda. His leadership credentials were challenged and his temperament tested like no time in his career.

"I’ve been hearing my name mentioned a little bit tonight. I wonder why?" Sanders quipped.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

The pile-on indeed reflected the new reality of the Democratic race for the White House. Riding a wave of enthusiasm among young voters and the strength of an increasingly diverse coalition, Sanders has won two of the first three contests and effectively tied in the third. He’s competing aggressively in South Carolina, which votes Saturday, and could pull away from the field in the all-important delegate lead in next week’s Super Tuesday contests.

For Sanders, this is new political terrain.

He’s spent 40 years in politics as an agitator and an outsider. He’s run for office as an independent and is a loner on Capitol Hill. He prides himself on being ideologically rigid and has been willing to criticize Democratic leaders, including former President Barack Obama, for what he’s seen as politically expedient compromises.

Now, four years after his insurgent White House bid made him a household name, he’s poised to become the Democratic standard-bearer, and the party’s pick to take on President Donald Trump in November.

Sanders’ strength has rattled many Democrats, who fear that his uncompromising liberal ideology will turn off voters in swing states, particularly suburban women who were crucial to the party’s takeover of the House in 2018. Donors and other party elites are anxiously hoping a more moderate candidate can overtake him in the coming weeks, but they concede those prospects are increasingly unlikely unless there’s a significant swing in the race.

His rivals tried to engineer a shift in the trajectory of the race in Tuesday’s debate. They pummeled the Vermont senator with a fierce onslaught of attacks and, at times, put him on the defensive.

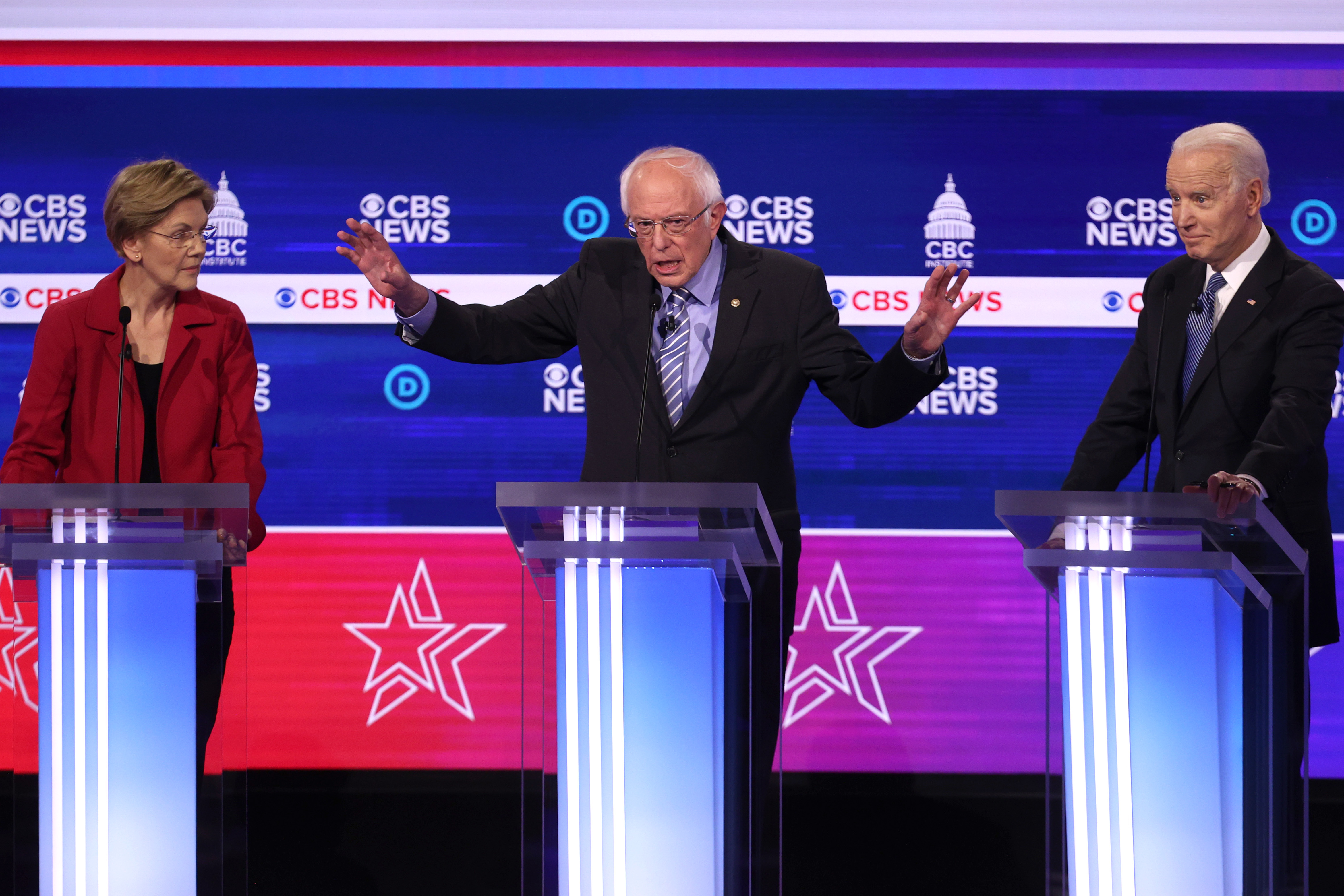

Former Vice President Joe Biden challenged Sanders’ effectiveness as a lawmaker, saying, "Bernie, in fact, hasn’t passed much of anything."

Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, accused Sanders of moving the goalposts on the costs of his sweeping policy proposals, including a "Medicare for All" health insurance system.

More Decision 2020 Coverage

Former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg charged that Sanders would not only lose to Trump, but his nomination would result in a "catastrophe" for Democratic House and Senate candidates running in more moderate states and districts.

"Can anybody in this room imagine moderate Republicans going over and voting for him?" Bloomberg asked.

Even Warren, a friend and ideological partner of Sanders, took him on vigorously for the first time, finally giving in to supporters who have urged her to explicitly cast herself as the more pragmatic and effective progressive candidate in the race.

"Bernie and I agree on a lot of things, but I think I would make a better president than Bernie," Warren said.

Sanders was prepared for the onslaught. When faced with questions about his electability, he rattled off polls showing him beating Trump in a head-to-head contest. When pressed about the feasibility of his pricey, government-backed policy agenda, he said it was a misconception that his policies are radical.

Yet Sanders was also forced to concede that he had made a "bad vote" in voting against stricter gun control legislation in the Senate.

And when he defended favorable comments he made recently about longtime Cuban leader Fidel Castro, he appeared caught off-guard when some in the audience in the debate hall in Charleston, South Carolina, jeered.

"Really? Really?" he challenged the crowd.

The intraparty offensive came as a relief to supporters of Sanders’ rivals, who have urgently been raising alarms about his prospects in the general election and warning that time is running out to block his path to the nomination.

"You saw him pressed, finally pressed by the other candidates," said Washington Mayor Muriel Bowser, a Bloomberg supporter.

The coming days will test whether the increased scrutiny of Sanders raised new doubts for voters. He’s not expected to win in South Carolina but, flush with cash, he is pouring resources into the state this week in hopes of pulling off a surprise and blocking out Biden, who needs a convincing win to continue his campaign.

But Sanders’ real focus is on the delegate-rich states that quickly follow March 3, including California, the primary’s biggest prize. A win there could start to put the race out of reach for the rest of the field.

Sanders’ team voiced confidence after the debate, arguing the senator benefited from being the focus of the field’s attention.

"They threw everything at him," said Nina Turner, a former Ohio state senator and a prominent Sanders backer. "He was in the center of that stage, where all the rest of them wanted to be."

Associated Press writers Bill Barrow and Meg Kinnard contributed to this report.