A judge on Wednesday approved a $626 million deal to settle lawsuits filed by Flint residents who found their tap water contaminated by lead following disastrous decisions to switch the city's water source and a failure to swiftly acknowledge the problem.

Most of the money — $600 million — is coming from the state of Michigan, which was accused of repeatedly overlooking the risks of using the Flint River without properly treating the water.

“The settlement reached here is a remarkable achievement for many reasons, not the least of which is that it sets forth a comprehensive compensation program and timeline that is consistent for every qualifying participant,” U.S. District Judge Judith Levy said in a 178-page opinion.

Attorneys are seeking as much as $200 million in legal fees from the overall settlement. Levy left that issue for another day.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

The deal makes money available to Flint children who were exposed to the water, adults who can show an injury, certain business owners and anyone who paid water bills. About 80% of what's left after legal fees is earmarked for children.

“This is a historic and momentous day for the residents of Flint, who will finally begin to see justice served," said Ted Leopold, one of the lead attorneys in the litigation.

Corey Stern, another key lawyer in the case, said he represented “many brave kids who did not deserve the tragedy put on them.”

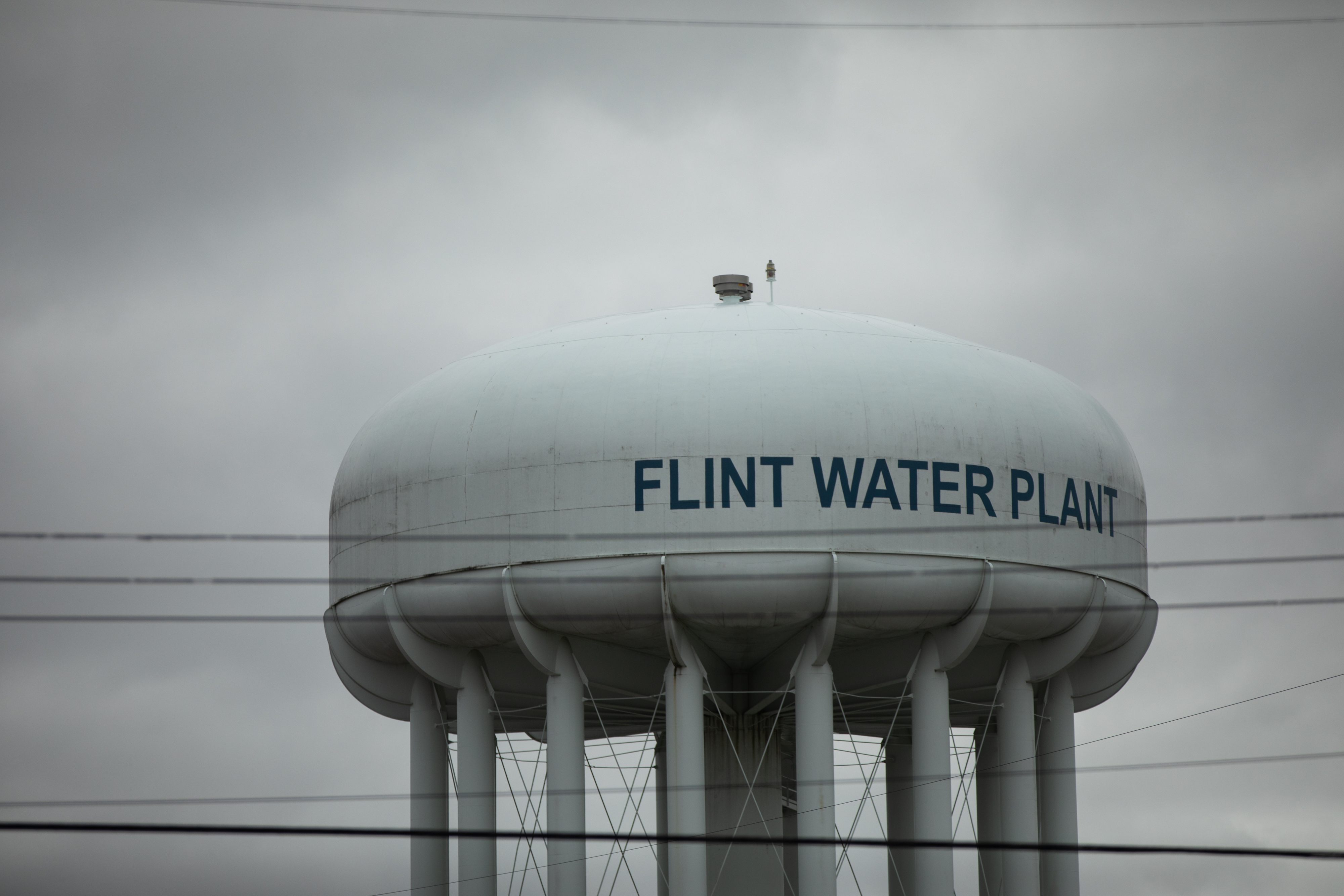

In a money-saving move, Flint managers appointed by then-Gov. Rick Snyder and regulators in his administration allowed the city to use the Flint River in 2014-15 while another pipeline was being built from Lake Huron. But the river water wasn't treated to reduce corrosion. Lead in old pipes broke off and flowed to homes as a result.

There is no safe level of lead. It can harm a child's brain development and cause attention and behavior problems.

Flint switched back to a Detroit regional water agency in fall 2015 after Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha publicly reported elevated lead levels in children.

Some critics said the disaster in the predominantly Black city was an example of environmental racism.

Flint is paying $20 million toward the settlement, while McLaren Health is paying $5 million and an engineering firm, Rowe Professional Services, is paying $1.25 million. Lawsuits still are pending against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, McLaren and other engineering firms.

The deal was announced in August 2020 by Attorney General Dana Nessel and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, both Democrats, who were elected in 2018 while the litigation was in state and federal courts.

The judge said it was “remarkable” that more than half of Flint's 81,000 residents have signed up for a share of the settlement. It's not clear just how much each child will receive. A claims process is next with families required to show records, such as blood tests or neurological results, and other evidence of injury.

Flint resident Melissa Mays, a 43-year-old social worker, said her three sons have had medical problems and learning challenges due to lead.

“Hopefully it’ll be enough to help kids with tutors and getting the medical care they need to help them recover from this,” Mays said. “A lot of this isn’t covered by insurance. These additional needs, they cost money.”

She considers the settlement a “win.”

“We’ve made history,” Mays said, "and hopefully it sets a precedent to maybe don’t poison people. It costs more in the long run.”

The Flint saga isn't over. Nine people, including Snyder, have been charged with crimes. They've pleaded not guilty and their cases are pending.

The state last week agreed to pay $300,000 to the former head of the drinking water division. An arbitrator said Liane Shekter Smith was wrongly fired for what happened in Flint.

___

AP reporter David Eggert in Lansing, Michigan, contributed to this story.