President Donald Trump and some members of Congress met Feb. 28 at the White House for a freewheeling discussion on how to reduce gun violence at schools. The meeting came two weeks after the mass shooting in Florida in which 17 people were killed, including 14 high school students.

Here we look at the facts regarding some of the issues that were raised during that meeting.

Do universal background checks reduce firearm deaths?

Sen. Christopher Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut, urged Trump to support federal legislation that would expand background checks of prospective gun buyers.

Currently, federal law requires background checks on those who buy guns from federally licensed firearm dealers. Murphy and the Democrats want to expand background checks to cover private sales by unlicensed individuals, including some of the sales that take place at gun shows and over the internet.

Murphy cited states that require universal background checks as evidence that such a federal law would reduce gun deaths.

Murphy: In states that have universal background checks, there are 35 percent less gun murders than in states that don’t have them.

U.S. & World

The day's top national and international news.

That’s true, but it doesn’t mean that universal background check laws have caused lower mortality rates. A causal relationship between such state laws and firearm deaths hasn’t been established by researchers.

In fact, Murphy is citing an average firearm mortality rate for states with universal background checks. But the states’ individual rates vary. Some of them have higher firearm mortality rates than states that don’t have universal background checks.

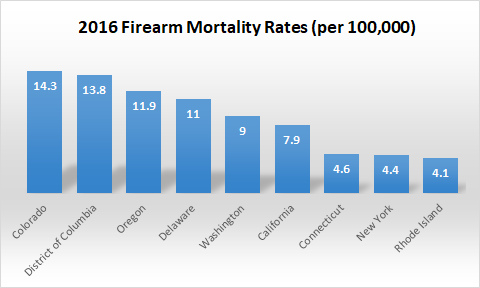

There are eight states and the District of Columbia that have laws in effect that require “universal background checks at the point of sale for all sales and transfers of all classes of firearms, whether they are purchased from a licensed dealer or an unlicensed seller,” according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. The average firearm mortality rate in those nine jurisdictions was 9 per 100,000 residents in 2016, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s 35 percent less than the states that don’t require universal background checks, as Murphy said.

Below are the rates for the eight states and the District of Columbia that required universal background checks in 2016.

Colorado, the District of Columbia and Oregon had rates higher than the national average, which was 11.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2016, according to the CDC.

They also had higher rates than Maine (8.3 deaths per 100,000), New Hampshire (9.3), and Vermont (11.1) — three states that have no state laws on background checks and received an “F” grade for the strength of their overall gun laws from the Giffords Law Center.

David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center, told us there haven’t been enough studies to say for sure that universal background checks reduce firearm deaths. But the studies that have been done suggest an association between such universal background checks and reduced firearm deaths, he said.

He referred us to a 2017 paper he coauthored that reviewed the available peer-reviewed research on gun control laws from 1970 to 2016. “We found evidence that stronger firearm laws are associated with reductions in firearm homicide rates,” the paper said. “The strongest evidence is for laws that strengthen background checks and that require a permit to purchase a firearm.”

The RAND Corp. on March 2 released several reports as part of its Gun Policy in America initiative, which looked at several thousand studies and identified 62 that met its criteria — “studies that offered some evidence, some estimate of the causal effect of [gun] policy” on several outcomes, Andrew Morral, a RAND senior behavioral scientist who led the project, told FactCheck.org.

The review of the scientific literature found “moderate” evidence (two studies in agreement) that background checks by licensed dealers may decrease firearm homicide rates, but whether private-seller background checks affect those rates was “uncertain.”

Do concealed-carry laws decrease violent crime?

Whether state concealed-carry laws — the right to carry a concealed firearm in public — cause an increase or decrease in gun violence remains unsettled.

At the bipartisan meeting, Republican Rep. Steve Scalise of Louisiana spoke about a House-passed measure that would allow people who have the right to carry a concealed handgun in one state to be able to carry a gun in other states that have concealed-carry laws. (All states have some form of concealed-carry permissions, though they vary in the requirements or restrictions.) “Look at the data,” Scalise said. “I know a lot of people want to dismiss concealed-carry permits. They do actually increase safety.”

Scalise’s office pointed us to statistics on the growth in concealed-carry permits, and the decades-long downturn in the national violent crime rate since it peaked in the early 1990s. But that doesn’t show any cause-and-effect. When we looked into this issue in 2012, we found there was academic disagreement on what impact concealed-carry laws had. Six years later, that’s still the case. And the body of research is largely inconclusive.

The RAND Corp. project also looked at studies on causal effects of concealed-carry laws. There was inconclusive evidence that such laws had an effect, in either direction, on mass shootings or suicides, and only “limited” evidence that such laws may increase unintentional injuries or violent crime overall. The “limited” evidence is just that — defined by RAND as one study meeting its criteria and not contradicted by studies “with equivalent or stronger methods.” In fact, RAND found inconclusive evidence on the impact on specific violent crimes: “Shall-issue concealed-carry laws have uncertain effects on total homicides, firearm homicides, robberies, assaults, and rapes,” it said, largely because studies found uncertain or inconsistent results.

“It’s hard to do research in this area,” Morral told us, citing three reasons that it’s difficult to prove causation of gun laws – “no funding, weak data and you can’t do experiments.”

We’ve explained before that while crime or homicides may go down after certain policies are implemented, it’s difficult to show that the policy caused the decline. Researchers can’t do real-life experiments with firearms. But setting that aside, Morral said, “The U.S. government does not invest heavily in collecting the kind of data you might want.”

And funding for gun research lags that for other causes of mortality. Morral referred to a recent paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found: “Between 2004 and 2015, gun violence research was substantially underfunded and understudied relative to other leading causes of death, based on mortality rates for each cause.”

The RAND project concluded: “With a few exceptions, there is a surprisingly limited base of rigorous scientific evidence concerning the effects of many commonly discussed gun policies.”

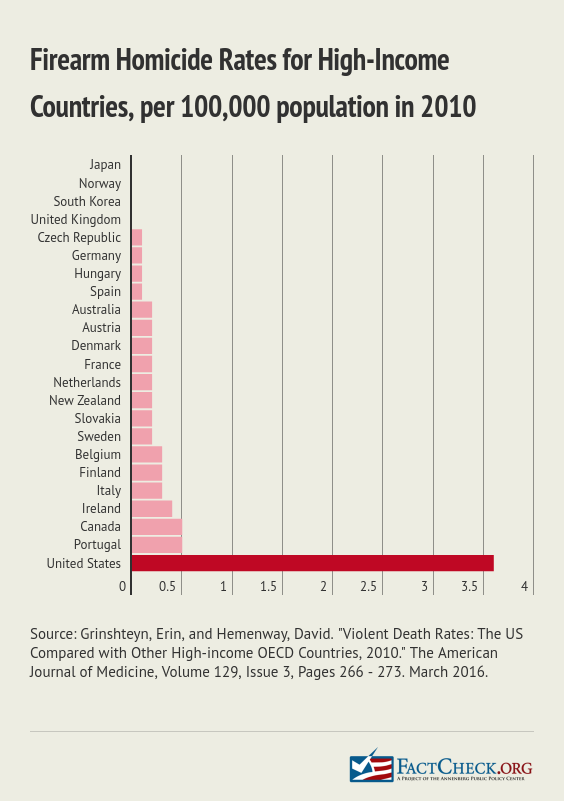

How does the U.S. gun homicide rate compare with other developed countries?

At the meeting, Murphy also said: “America has a gun violence rate that is 20 times that of every other industrialized country in the world.” His wording was imprecise.

A spokesman for the senator said he was referring to a study on violent death rates published in the American Journal of Medicine in March 2016. It found the “U.S. gun homicide rate” in 2010 was 25 times higher than the rate for more than 20 other “populous, high-income countries” combined, not individually.

The authors of that paper, Erin Grinshteyn and David Hemenway, used mortality data from the World Health Organization to compare the U.S. with 22 other high-income countries, with at least 1 million inhabitants, that also belonged to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development in 2010. That was the most recent year with “complete data for the greatest number of countries,” the paper says.

They concluded: “In 2010, the US homicide rate was 7.0 times higher than the other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher.”

That comparison was based on the aggregated gun homicide rate for only the non-U.S. nations examined, not “every other industrialized country,” Grinshteyn told us in an email. And it doesn’t mean the U.S. rate was 25 times higher than the rate for each of the studied countries, as Murphy’s statement may have suggested to some.

For example, the U.S. gun homicide rate of 3.6 deaths per 100,000 population in 2010 was about seven times higher than the rates in Canada and Portugal, about nine times higher than the rate in Ireland, and about 12 times higher than the rates in Belgium and Italy.

On the other hand, Grinshteyn said, the data show America’s rate was 82 times higher than the rate in the United Kingdom, 88.3 times higher than the rate in Norway, 513.8 times higher than the rate in Japan, and 594.7 times higher than in South Korea, which had the lowest gun homicide rate of all the countries included.

The combined gun homicide rate for all 22 nations was 0.1434 deaths per 100,000 population, Grinshteyn said, and the U.S. rate was 25 times higher.

That said, Murphy still has a point about the large gap between the U.S. and other similarly developed nations.

“The United States has an enormous firearm problem compared with other high-income countries,” Grinshteyn and Hemenway wrote in their analysis. “In the United States, the firearm homicide rate is 25 times higher, the firearm suicide rate is 8 times higher, and the unintentional gun death rate is more than 6 times higher. Of all firearm deaths in all these countries, more than 80% occur in the United States.”

Are most firearm homicides committed with stolen guns?

During the White House meeting, Republican Rep. John Rutherford of Florida said “stolen guns kill more people than guns that are bought legally.” There is no research to prove that.

Rutherford’s office pointed us to a Washington Post story about a study on guns recovered by Pittsburgh police. But an author of that study says Rutherford got it wrong.

“There is no data in our study that would support that statement,” the study’s lead author, Anthony Fabio of the University of Pittsburgh, told us in a phone interview.

The 2016 study — “Gaps continue in firearm surveillance: Evidence from a large U.S. City Bureau of Police” — found that in 2008 most perpetrators, 79 percent, were carrying guns that did not belong to them. But that doesn’t mean they were all stolen or even illegally obtained, and it doesn’t mean that they were used to kill people.

The researchers concluded about 33 percent of the guns were reported stolen when police contacted the gun owners (more than 40 percent of those stolen guns had not been reported stolen prior to that). Another 22 percent were not stolen. In a large proportion of cases — 44 percent — it was unknown or could not be determined if the gun was stolen.

The study was not limited to guns used to commit homicides. The authors did not know what crimes the recovered guns were used for. In other words, the study does not back up Rutherford’s statement about the prevalence of stolen guns being used in murders.

It is certainly true that a large percentage of guns that are used to kill someone were acquired illegally, said Philip Cook, a public policy professor at Duke University. If nothing else, he said, research he did in 2005 shows that more than 40 percent of those convicted of homicide had at least one prior felony conviction that would prohibit them from owning a gun.

“But most such illegal transactions do not involve stolen guns, as far as we know,” Cook told us.

Cook, who is currently doing research on gun theft, told us via email that he was unaware of any evidence that would support Rutherford’s statement that “stolen guns kill more people than guns that are bought legally.”

A 1986 study of nearly 2,000 convicted felons in 10 state prisons by researchers James Wright and Peter Rossi found that nearly a third of those reported they had directly stolen their most recent handguns. About 44 percent of their guns were obtained from friends or family, and 26 percent from “gray or black market sources,” the report states. Wright said the study concluded that “70 percent of the most recent handguns possessed by this sample were definitely or probably stolen.” But the study’s authors could not confirm that this percentage definitely represented stolen guns.

“So the more general point, that improper storage of guns by legal users puts an awful lot of firearms into criminal hands, is no doubt correct,” Wright told us via email.

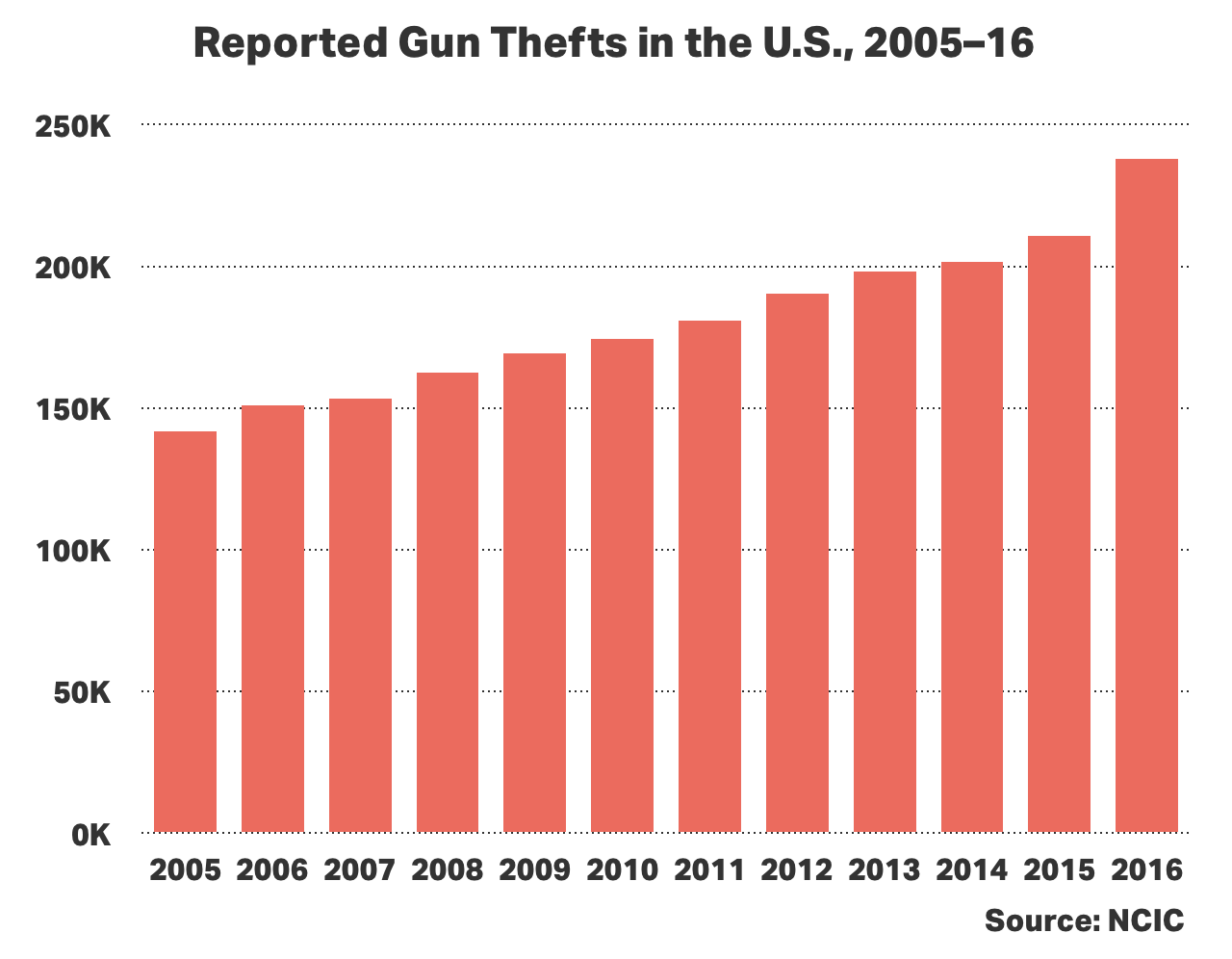

Federal data back that up.

The Trace reported that 237,000 guns were reported stolen in the U.S. in 2016, up 68 percent from 2005, according to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center. Those records show nearly 2 million weapons were reported stolen over the last decade. One caveat: In 2005, fewer states had laws requiring gun owners to report missing firearms, and The Trace noted that “[w]hen asked if the increase could be partially attributed to a growing number of law enforcement agencies reporting stolen guns, an NCIC spokesperson said only that ‘participation varies.'”

The actual number of stolen firearms is likely much higher, the report states, since many gun thefts go unreported.

Federal law requires licensed dealers to report stolen or lost guns, but not individual gun owners. Only 11 states and the District of Columbia require gun owners to report stolen firearms, according to the Giffords Law Center.

The graphic below was part of The Trace article.

So Rutherford has hit upon a growing problem in the U.S. with stolen guns, even though there is no hard evidence that more stolen guns are used in homicides than guns that are purchased legally.

Fabio, the lead author of the study on recovered guns in Pittsburgh, said one of the biggest takeaways from his study is that there is a dearth of good data and research about firearms. That echoes the findings of the RAND project on gun violence.

Since the late 1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been wary of studying gun issues after NRA lobbyists convinced Congress to cut into its funding after a series of studies in the mid-1990s were viewed by the NRA as advocating gun control. Referred to as the Dickey amendment, a warning has accompanied appropriations bills, saying that “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”

As a result, Fabio said, “There’s not a lot of money for research with the word ‘firearm’ in it.”

Did the law banning certain types of semiautomatic weapons from 1994 to 2004 reduce gun violence and deaths?

At the meeting, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, a Democrat from California, gave Trump a letter and said: “This is when the 10-year assault weapon ban was in — how incidents and deaths dropped. When it ended, you see it going up.”

Feinstein’s office told us she was referring to a Washington Post article about “Rampage Nation,” a 2016 book by Louis Klarevas. The author collected data on mass shootings — those involving six or more firearm deaths — for a 50-year period in an effort to assess the impact of the 1994 ban — which prohibited the sale of an estimated 118 models of semiautomatic weapons from 1994 to 2004.

Klarevas identified 12 mass shootings that resulted in 89 deaths when the ban was in effect, down from 19 incidents and 155 deaths in the previous 10-year period, from 1984 to 1994, the Post article says.

Federally funded research, however, did not credit the 1994 ban with reducing gun violence.

As we have written before, the Department of Justice funded a series of three studies on the effectiveness of the law that concluded with a 2004 study led by Christopher S. Koper, “An Updated Assessment of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban: Impacts on Gun Markets and Gun Violence, 1994-2003.”

That final report said the ban was successful in reducing crimes committed with assault weapons, or AWs. However, that decline was likely offset “by steady or rising use of non-banned semiautomatics with [large-capacity magazines], which are used in crime much more frequently than AWs,” the report said.

“Therefore, we cannot clearly credit the ban with any of the nation’s recent drop in gun violence,” the report concluded.

What happened after the federal ban expired?

As Feinstein referenced, Klarevas reported an increase in mass murders. In the 10-year period after the ban expired, the number of mass shootings increased by 183 percent (from 12 to 34) and the number of deaths increased by 239 percent (from 89 to 302), according to Klarevas.

In a paper published last year in the Journal of Urban Health, Koper and his colleagues said the “limited” data available on the type of guns used in mass shootings “suggests” an increase in the use of “assault weapons and other high-capacity semiautomatics.”

The researchers said that “detailed weapon information could not be found in public sources for many” of the mass murders, which they defined as four or more firearm deaths, not including the shooter, in a single incident.

Koper et al, Oct. 2, 2017: Estimates for firearm mass murders are very imprecise due to lack of data on the guns and magazines used in these cases, but available information suggests that AWs and other high-capacity semiautomatics are involved in as many as 57% of such incidents.

That study also found an increased use of high-capacity semiautomatics in crime in general.

Using local crime data from three cities and FBI data on law enforcement murders nationwide, Koper and his colleagues found that such high-powered guns “have grown from 33[%] to 112% as a share of crime guns since the expiration of the federal ban — a trend that has coincided with recent growth in shootings nationwide.”

At the high end, the percentage of semiautomatics used in crimes in Richmond, Virginia, increased from 10.4 percent in 2003 and 2004 to 22 percent in 2008 and 2009, an increase of 111.5 percent, the report said. The 33 percent figure represents the increase in the number of law enforcement officers killed by high-capacity semiautomatics, up from 30.4 percent in 2003 through 2007 to 40.6 percent in 2009 through 2013.

Would restoring the ban, as proposed by Feinstein, reduce mass shootings and gun violence in general? That’s unclear.

David Hemenway, the director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, told us last year that an assault weapons ban may reduce mass shootings, but it would be unlikely to reduce gun deaths overall.

For a 2017 paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Hemenway and his colleagues reviewed the available research on the association between firearm laws and preventing firearm homicides. Specifically, they reviewed four studies — including the 2004 federally funded study led by Koper — regarding bans on military-style weapons.

That paper said the reduction in firearm homicide rates identified by Koper et al during the federal gun ban period “was not statistically significant.” The three other studies “examined laws banning assault weapons in the context of other firearm-related laws; none found a decrease in firearm homicides,” the paper said.

“Specific laws directed at … the banning of military-style assault weapons were not associated with changes in firearm homicide rates,” the researchers concluded.

After the paper was published, Hemenway told us last year, “I doubt that banning AR-15 type weapons has much effect on overall gun deaths since these type of guns are not often used in suicides, homicide or for accidents. Reducing the accessibility of AR-15 type weapons might reduce mass shooting incidents and fatalities.”

The RAND project looked at studies on state assault-weapons bans and found “inconclusive” evidence that they affected mass shootings or homicides overall.