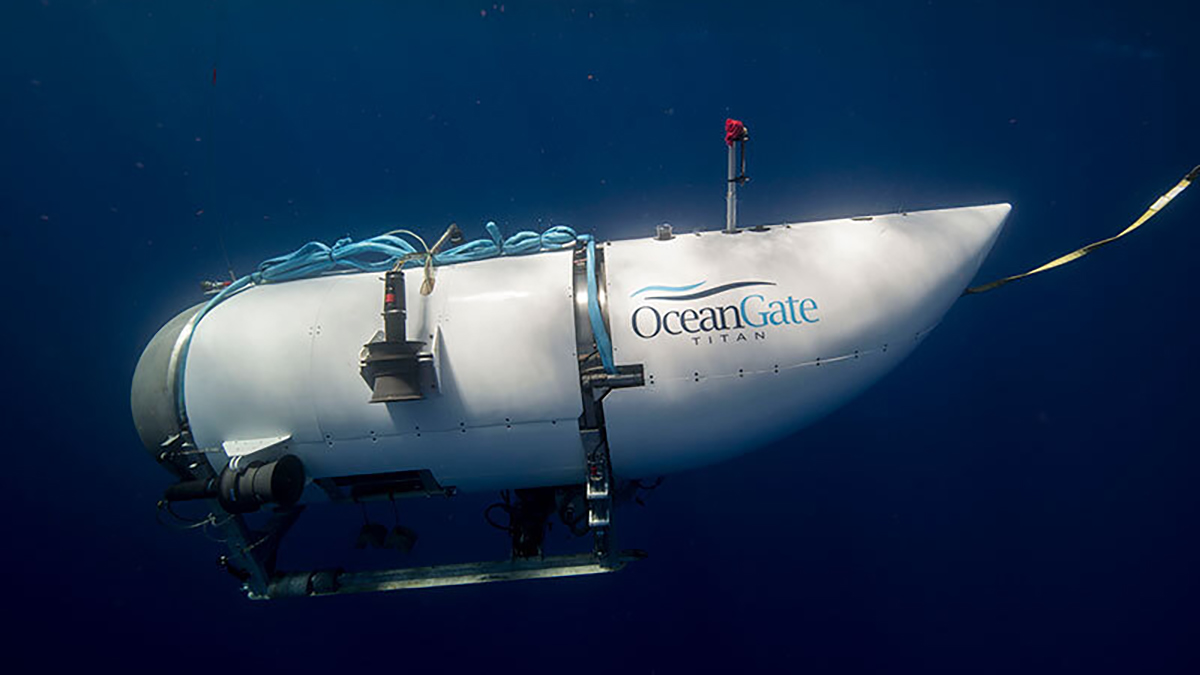

Debris was recovered from the Titan submersible, and the Coast Guard believes human remains have been found.

Debris from the lost submersible Titan has been returned to land after a fatal implosion during its voyage to the wreck of the Titanic captured the world's attention last week.

The return of the debris to port in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, is a key piece of the investigation into why the submersible imploded, killing all five people on board. The U.S. Coast Guard said Tuesday that the debris included presumed human remains which will be examined by medical experts.

Twisted chunks of the 22-foot submersible were unloaded at a Canadian Coast Guard pier on Wednesday.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

Horizon Arctic, a Canadian ship, carried a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, to search the ocean floor near the Titanic wreck for pieces of the submersible. Pelagic Research Services, a company with offices in Massachusetts and New York that owns the ROV, said on Wednesday that it has completed offshore operations.

Pelagic Research Services' team is “still on mission” and cannot comment on the ongoing Titan investigation, which involves several government agencies in the U.S. and Canada, said Jeff Mahoney, a spokesperson for the company.

“They have been working around the clock now for ten days, through the physical and mental challenges of this operation, and are anxious to finish the mission and return to their loved ones,” Mahoney said.

Debris from the Titan was located about 12,500 feet (3,810 meters) underwater and roughly 1,600 feet (488 meters) from the Titanic on the ocean floor, the Coast Guard said last week. The Coast Guard is leading the investigation into why the submersible imploded during its June 18 descent. Officials announced on June 22 that the submersible had imploded and all five people on board were dead.

The Coast Guard has convened a Marine Board of Investigation into the implosion. That is the highest level of investigation conducted by the Coast Guard.

One of the experts the Coast Guard consulted with during the search said analyzing the physical material of recovered debris could reveal important clues about what happened to the Titan. And there could be electronic data, said Carl Hartsfield of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“Certainly all the instruments on any deep sea vehicle, they record data. They pass up data. So the question is, is there any data available? And I really don’t know the answer to that question,” he said Monday.

Representatives for Horizon Arctic did not respond to requests for comment.

Coast Guard representatives declined to comment on the investigation or the return of debris to shore on Wednesday. Representatives for the National Transportation Safety Board and Transportation Safety Board of Canada, which are both involved in the investigation, also declined to comment.

The National Transportation Safety Board has said the Coast Guard has declared the loss of the Titan submersible to be a “major marine casualty” and the Coast Guard will lead the investigation.

“We are not able to provide any additional information at this time as the investigation is ongoing,” said Liam MacDonald, a spokesperson for the Transportation Safety Board of Canada.

OceanGate Expeditions, the company that owned and operated the Titan, is based in the U.S. but the submersible was registered in the Bahamas. OceanGate is based in Everett, Washington, but closed when the Titan was found. Meanwhile, the Titan’s mother ship, the Polar Prince, was from Canada, and those killed were from England, Pakistan, France, and the U.S.

Killed in the implosion were Ocean Gate CEO and pilot Stockton Rush; two members of a prominent Pakistani family, Shahzada Dawood and his son Suleman Dawood; British adventurer Hamish Harding; and Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet.

The operator charged passengers $250,000 each to participate in the voyage. The implosion of the Titan has raised questions about the safety of private undersea exploration operations. The Coast Guard also wants to use the investigation to improve safety of submersibles.

Associated Press writer Holly Ramer in Concord, New Hampshire, contributed to this report.