A few months after Election Day 2020, a sheriff’s deputy and a second man walked into the office of the Rutland Charter Township clerk in southwest Michigan. Clad in dress clothes, the man identified himself as a private investigator and said he was conducting a criminal investigation into election fraud, NBC News reported.

“It was kind of a shock,” recalled the clerk, Robin Hawthorne. “We didn’t have any discrepancies. We passed the canvass with flying colors, so it was like, ‘What are they doing here?’”

Hawthorne is a Republican in a solid-red township of 4,100 people. She had been Rutland Charter’s clerk since 2001 and had never encountered anything like this.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

Hawthorne answered the private investigator’s questions, she said, as the deputy recorded the conversation on his phone. But when they asked to see her vote-counting machines, she was adamant.

You can look at them, she recalled telling the men, but you can’t touch anything.

They got up to leave instead. But before doing so, Hawthorne said, they insisted that she not mention their visit to anybody to protect the investigation.

U.S. & World

The day's top national and international news.

“I was like bull crap,” she said. “You’re not going to come in here, grill me like this and I’m not going to find out what’s going on.”

She soon learned that the deputy and the private investigator had visited other township offices as part of an effort to find evidence of election fraud. And the man responsible for it was the top lawman in the area — Barry County Sheriff Dar Leaf.

Leaf fashions himself as a “constitutional sheriff.” Sheriffs like him see themselves as holding supreme authority in their counties, exceeding that of state and federal law enforcement officials. They have become prominent figures in the election denial movement, and according to critics, among the most dangerous. “Constitutional sheriffs” believe they have the authority to seize voting machines, assemble armed posses to patrol near polling stations and refuse to enforce any law they view to be unconstitutional.

“This is vigilantism hiding behind a badge,” said Matt Sanderson, an election lawyer in Washington. “No official in this country has unchecked power, and it’s absurd to say that a local sheriff of all people would have some constitutional superpower to disregard courts and laws in pursuit of an extralegal agenda.”

Even though efforts to prove election fraud in 2020 fizzled out, constitutional sheriffs have only grown in stature in recent years. Frank Figliuzzi, a former FBI assistant director for counterintelligence, said he fears the possibility of one of these sheriffs interfering in the election process in a pivotal state like Michigan or Wisconsin.

“The worst case scenario is in a key swing state one of these knucklehead sheriffs tries, and somehow succeeds, in seizing ballots or stopping the voting process,” Figliuzzi said. “That allows Trump to claim victory and then their trained militia members come in and do who knows what.”

Leaf did not respond to phone or email messages seeking comment.

Trump world celebrities

It’s difficult to say how many constitutional sheriffs exist in the U.S. The most prominent group, the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, was founded in 2011 by Richard Mack, a former Arizona sheriff and member of the Oath Keepers militia. He has claimed that 10% of the nation’s 3,000 sheriffs are members, along with 10,000 ordinary citizens.

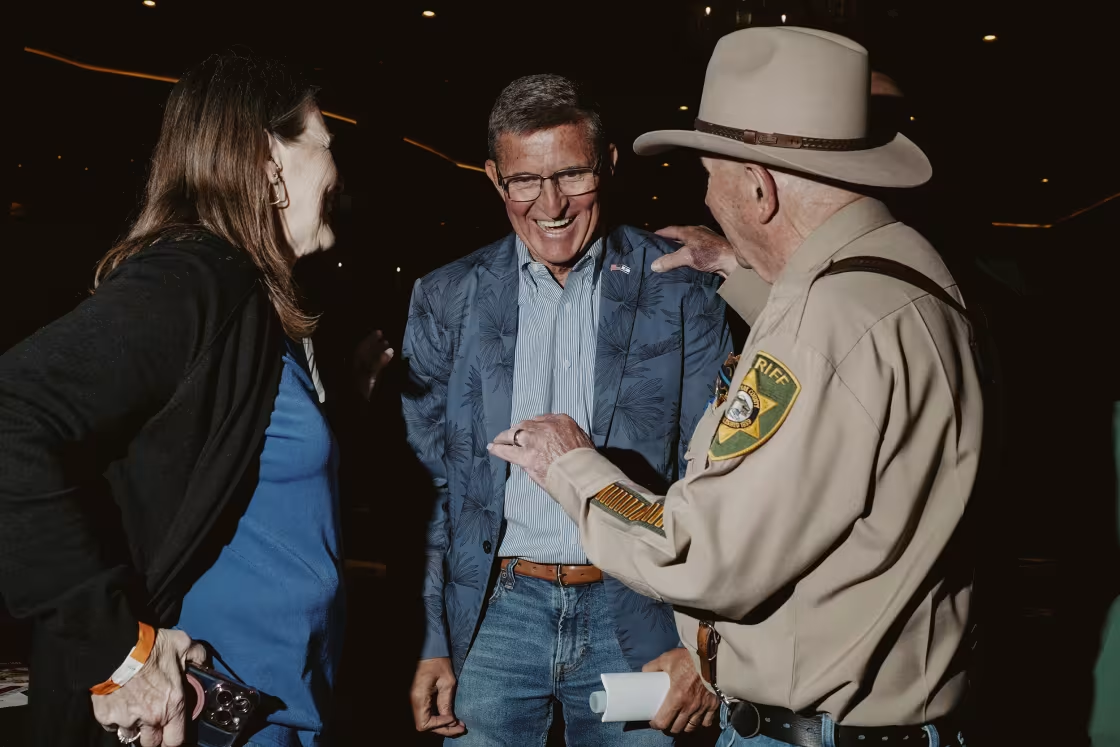

The group held a conference in Las Vegas last May, drawing a crowd of current and former sheriffs as well as election-denying Trump-world celebrities like MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell and former national security adviser Michael Flynn. Mack delivered a speech in which he called federal and state agencies “the gestapo of America” and said “the sheriffs are going to have to stop it.”

The 2020 election has become a central focus. Multiple sheriffs aligned with Mack, including Chris Schmaling of Racine County, Wisconsin, and Calvin Hayden of Johnson County, Kansas, have trumpeted their ongoing election fraud investigations.

“I’ve got a cyber guy,” Hayden said at a 2022 conference, according to the Associated Press. “I sent him through to start evaluating what’s going on with the machines.”

But perhaps no sheriffs in Mack's group have drawn as much attention as Dar Leaf in Michigan.

Elected in 2003, Leaf first made national headlines a month before the 2020 election when he weighed in on the actions of 13 men charged with plotting to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

“A lot of people are angry with the governor and they want her arrested,” Leaf told Fox 17 News in Grand Rapids. “So were they trying to arrest, or was it a kidnap attempt? Because you can still, in Michigan, if it’s a felony, you can make a felony arrest.”

The 2020 election was a seminal moment for Leaf. After Joe Biden was declared the winner, Trump claimed without evidence that the election had been rigged against him.

In Leaf and other members of the constitutional sheriffs movement, Trump attracted allies willing to take action. Leaf worked with Stefanie Lambert, a Detroit lawyer who was part of the Trump team led by Sidney Powell, a conspiracy theory-espousing attorney who filed several frivolous lawsuits alleging widespread voter fraud and rigged machines that flipped votes from Trump to Biden.

Leaf took legal action on his own in early December 2020, seeking an emergency order to stop local clerks from deleting certain election records, as is standard procedure. The chief judge of the federal court in Grand Rapids denied the request in a scathing order.

Leaf and his co-plaintiffs “invite the court to make speculative leaps toward a hazy and nebulous inference that there has been numerous instances of election fraud and that defendants are destroying the evidence,” the judge wrote. “There is simply nothing of record to infer as much.”

During this period, Doug Van Essen, a lawyer in Grand Rapids, said he received a call from a sheriff in a nearby county with a pointed question: “Would you get Dar off my back?”

The sheriff said Leaf wanted him to talk to an Army colonel who allegedly had evidence of election fraud in one of the reddest counties in the state. Van Essen said he agreed to call the colonel, and then found himself listening to a man spouting nonsense.

Biden garnered 40% more votes than Barack Obama did in the 2008 election, the colonel said, according to Van Essen.

“That was true,” Van Essen said. “But this was the fastest-growing county in Michigan, and Trump got 40% more votes than (John) McCain. It was the same percentage.”

“That’s the kind of so-called evidence they had,” added Van Essen, who considers himself a traditional Republican and Leaf “an embarrassment.”

Good ol’ boys

It was in early 2021 that Leaf’s deputy and the private investigator marched into Hawthorne’s office in Rutland Charter Township. Trump had soundly defeated Biden in Barry County, garnering 65% of the vote, but lost the state of Michigan by 154,000 votes.

Leaf’s deputy and private investigator grilled several town clerks and managed to seize one voting machine, according to local reports and the Michigan Attorney General’s Office. He had also sought warrants to seize vote tabulators in Barry County and Woodlawn Township, according to documents obtained by Reuters.

Leaf began touting his election fraud investigation at public events, drawing cheers and applause. He has claimed that “Serbian foreign nationals” remotely accessed voting machines in Michigan, and at other times that Venezuelans had programmed the machines to jam.

For Hawthorne, it’s only brought headaches and dismay.

“He’s stirred up Barry County terrible,” said Hawthorne. “It’s sad to see that people are not trusting me to do my job. That’s a sacred duty of mine and I take it seriously.”

At an event in July 2021, Leaf said he launched the probe after a retired sergeant from his office came to him with “some documentation” from “the MyPillow guy” — Lindell, an outspoken election denier and conspiracy theorist.

Leaf added that the voter fraud investigation was the “biggest task I got going on right now.”

“I’m hoping that other sheriffs will catch on, actually get a backbone and do their own investigations,” he said.

Leaf’s has stretched on for four years but has yet to produce clear evidence of fraud or misconduct. In a twist, the sheriff and his associates found themselves under investigation by the state attorney general for their role in a plot to access voting machines across Michigan. In August 2023, three people were charged in the scheme — including Lambert, the Trump team lawyer Leaf worked with — but not Leaf himself.

The special prosecutor who brought the case, D.J. Hilson, said in a statement at the time that the decision not to charge Leaf and others was based on an evaluation of the law and “careful consideration of the totality of the evidence gathered by investigators.”

Lambert, who has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial, said in an email that she didn’t violate the law. She described herself as an attorney who began working for Leaf after the 2020 election.

Leaf, meanwhile, is still focused on digging up election fraud from four years ago but appears to have moved beyond Michigan. Just last week, he posted a memo on his social media pages that said he’s made “referrals for criminal investigation” to the Texas Attorney General’s Office.

“He’s still out there talking, blabbering, stirring up the masses,” said Hawthorne, the Rutland Charter clerk. “People are coming up here saying they’re sure the machines are flipping the vote.”

Hawthorne said early voting has gone smoothly but she’s worried about the period after the election if Vice President Kamala Harris is declared the winner.

“There’s a lot of good ol’ boys around here who think what happened on Jan. 6 was great,” Hawthorne said.

The veteran clerk said she’s hoping things remain calm in her little corner of Michigan. But one thing is certain: If there is an emergency, she’s not going to call the sheriff’s office.

“I’m calling the state police,” Hawthorne said. “I don’t trust the Barry County Sheriff’s Office.”

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com. More from NBC News: