Charles Spencer, the younger brother of the late Princess Diana, was only 8 when he was sent away to an all-boys boarding school in the English countryside.

Maidwell Hall catered to the upper crust of British society. But Spencer says what he experienced from the staff — blows to the head with a signet ring, a beating with metal-spiked cricket cleats and sexual abuse by a female caretaker — has haunted him for nearly 50 years, he told NBC News in an exclusive interview.

“We were like prisoners,” Spencer said in his first interview since the publication of his new book, “A Very Private School.” “We were prey to very bad people’s worst instincts.”

Spencer attended the school until age 13 and went on to become a historian, podcaster and bestselling author. He said he felt compelled to write the book after several former students confided in him their dark memories and lasting trauma.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

“Their stories are so devastating, and they are stories they’ve never told anyone,” said Spencer, who interviewed about two dozen former classmates who attended the school with him in the mid-1970s.

“As soon as I got stuck into the writing of it and interviewed more and more people, I realized that this was a serious scandal.”

A Maidwell Hall spokesperson said the school is taking Spencer’s allegations seriously and has reached out to the local authority charged with protecting children in the U.K., the local authority designated officer, or LADO.

U.S. & World

The day's top national and international news.

“We will follow their guidance on what we do from this point,” the spokesperson said. “We would encourage anyone with similar experiences to come forward and contact the LADO or the police.”

Spencer, the godson of Queen Elizabeth II and the uncle of the future king, was born into privilege but still endured a complicated childhood.

He was 2 when his mother divorced his father and left the family home. His father was loving but withdrawn and seemingly depressed, Spencer said. Diana became his protector. On his first day at their local day school, little Diana insisted on leaving her classroom to check in on him.

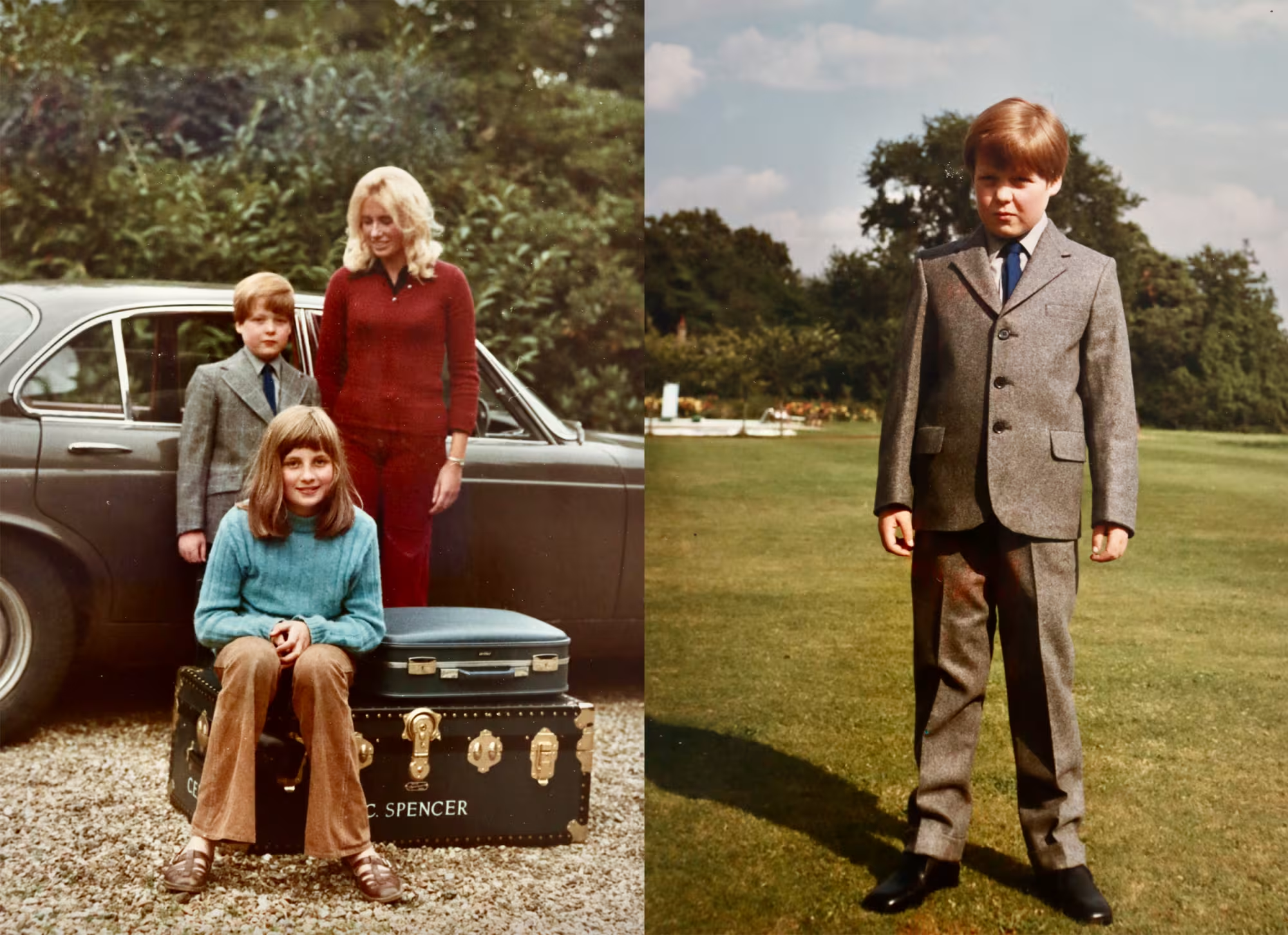

“Four years after that," he said, “I was 8 being sent off to a brutal place by myself, saying goodbye to Diana, who I grew up with, and my nanny, who was my mother substitute, standing by my school trunk, the big chest with all of my stuff in it.”

Spencer arrived at the school in 1972.

Maidwell Hall sits on sprawling, picturesque grounds in Northamptonshire, about two hours north of London. At the heart of the estate is a 17th century manor house. The roughly 75 boys at the school all lived on the grounds surrounded by stone walls.

Spencer soon learned that inside those walls, violence and cruelty reigned.

Boys were routinely beaten with canes for minor transgressions. Others were struck with heavy window poles, Spencer said.

It was not uncommon to see students in the communal shower rooms with split-open skin and bloody welts on their buttocks from the canings.

Spencer blames the school’s headmaster, John Alexander Hector Porch, for its culture of cruelty. Porch ran Maidwell the entire time Spencer attended (he is now deceased).

“The headmaster was, in my view, a pedophile and a sadist,” Spencer said. “And he staffed the school with either people who were going along with what he was doing or who were going to be mute about it.”

Porch would force the young boys to drop their pants and their underwear and lie across his lap to be whipped. He sometimes fondled their genitals in the process, Spencer said.

Many of the boys selected for the beatings were the same physical type, a “type that the headmaster seemed to like,” Spencer said.

“He liked athletic boys, and he liked blond boys.”

Spencer said that he wasn’t whipped by Porch but that he was subjected to other forms of brutality by the headmaster. Porch’s “usual weapon” was a slipper, and even that was painful. “But it wasn’t the cutting pain of the cane,” Spencer said.

The abuse wasn’t spoken of in school. It also remained hidden from parents in part, Spencer believes, because of the messages the headmaster and others drilled into the boys: Don’t show emotion, and don’t speak of what happens at Maidwell.

“The most important code of this very flawed regime that I was part of was never to tell tales, not to ‘sneak,’ as they call it,” Spencer said. “I think all of this was very much designed to make you not talk about it and really to try and suppress the memories.”

Porch inspired terror, but he wasn’t the only adult Spencer and the other boys feared.

One day, Spencer was alone inside a locker room changing his clothes to play cricket when a male teacher walked in. “He just grabbed me and threw me over his knee,” Spencer said.

Then the man picked up Spencer’s spiked cricket cleat.

“He beat me and beat me, puncturing my behind, and then just moved away,” Spencer said. “He found an easy victim to assault.”

Another teacher seemed to take special pleasure in inflicting pain on Spencer. This man often railed against wealth inequality, and Spencer now realizes his moneyed upbringing made him an obvious target.

“He’d hit me a lot,” Spencer said.

But it wasn’t the man’s fists that did the most damage. It was his signet ring.

“He used to do this very clever maneuver where he’d hit me and then with the signet ring cut me in the scalp,” Spencer said. “It would bleed and crust.”

“It’s astonishing to me now that you could direct that venom and physical brutality towards children openly and no one says anything,” Spencer added.

Still, Spencer’s most enduring trauma was caused by one of the least intimidating figures on the staff, a young woman charged with taking care of the boys.

Spencer was 11 when he moved into a remote sleeping area that was under her charge.

“It would start with her coming round after the lights were turned out in the dormitory and giving any boy awake maybe cookies, maybe grapes, something like that,” Spencer said.

In time, she began to come around to Spencer’s bed when others were asleep but not to sneak him snacks. She would kiss him. Passionately.

“French kiss for ages,” Spencer said. “If I was 17, 18, it would be a different thing. But I was 11, and it was so confusing.”

Looking back, he says, “of course, it was terrible.”

But at the time, “I’m embarrassed to say it was thrilling, especially in an emotional desert such as that place was,” Spencer said.

Unlike some of the boys, the woman didn’t have sexual intercourse with Spencer. But he said she did touch his private parts and force him to touch hers.

She was also a “master of manipulation,” he wrote in the book. “With a sudden huff or a deliberate turning of her back, she would publicly shun one of the children she was molesting.”

When the woman announced that she was leaving the school, Spencer said, he was shattered.

“I remember cutting myself,” he said. “I thought, if I hurt myself enough, then God will let her stay.”

But her departure wasn’t the end of the experience for him.

During a holiday break a few months later, Spencer, then 12, was in Italy with his mother and stepfather. They were near their hotel when they pointed out a prostitute who was standing outside.

He later snuck out of the hotel and tracked down the sex worker, paying for her services with “pocket money.”

“I lost my virginity to a prostitute,” he said. “I see that as the completion of what she” — the woman at Maidwell — “had done to me.”

He told no one until he was 42 and seeing a therapist. It came out after the therapist asked him to whisper something he had never told anyone. “I said, ‘I was sexually abused by a woman when I was a child.’”

He didn’t tell his wife about the sexual abuse until he began writing the book.

The stories Spencer heard from his classmates were brutal. One of them told him that he still has scars on his buttocks from the last time he was beaten in 1977.

Spencer said he would often return home after such interviews feeling so emotionally exhausted he could barely move. It took him five years to complete the interviews and write the book.

“What was so overwhelming was going to meet people who I thought I knew, who lived this very intense life with me when we were children,” Spencer said. “They told me about how poorly they were sexually, physically or emotionally abused, and it was devastating.”

He spoke to NBC News at his sweeping Althorp estate, which has been in the family since 1508. The property encompasses more than 10,000 acres of farm and parkland, part of which he has devoted to a garden temple surrounded by water as Diana’s final resting place.

“I told a friend about this recently,” Spencer said, referring to the abuse he suffered at Maidwell. “And [the friend] said, ‘I just can’t believe you weren’t protected,’ as if coming from this incredibly privileged background somehow would be protection against pedophiles.”

The Maidwell Hall spokesperson described the experiences Spencer and other alumni had at the school as “sobering.”

“We are sorry that was their experience,” the spokesperson said. “It is difficult to read about practices which were, sadly, sometimes believed to be normal and acceptable at that time.”

Spencer acknowledged that he received an excellent education at Maidwell Hall, and, like many other students, he went on to attend two other elite schools, Eton and Oxford.

He emphasized that he isn’t opposed to boarding schools for older children, but he does believe it shouldn’t be legal to send children away to them as young as 8.

Maidwell Hall “was built on a lie common to institutions of its type: on the cock-and-bull notion that children were better off under its roof, learning to be biddable, influential members of society, rather than living as we should have done, as nature intended, with our families,” he wrote in the book.

He wrote the book not for sympathy, he said, but to help all of those who have suffered as children in abusive settings.

Spencer dedicates “A Very Private School” to Buzz, the nickname his family gave him before he went away to Maidwell, because he had the “happy effervescence of a bee.”

“That was the boy who had part of him snuffed out during those five years at the school,” Spencer said. “So I wanted to reconnect with the carefree happy little guy I was before I was sent to this place.”

He said he feels he’s well on the way to reclaiming that lost childhood.

This story originally appeared on NBCNews.com. Read more from NBC News: