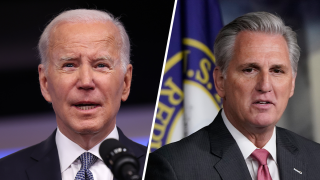

President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy met face-to-face Wednesday for more than an hour of highly anticipated spending talks — "a good first meeting," the new Republican leader said — but expectations were low for significant progress as GOP lawmakers push for steep budget cuts in a deal to prevent a national debt limit crisis.

Biden has resisted direct spending negotiations linked to vital action raising the nation's legal debt ceiling, warning against potentially throwing the economy into chaos. But the Republican leader all but invited himself to the White House to start the conversation before a summer debt deadline. McCarthy emerged saying the two had agreed to meet again

“No agreement, no promises except we will continue this conversation,” McCarthy told reporters outside the White House.

“We both have different perspectives on this, but I thought this was a good meeting,” he said.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

The House speaker arrived for the afternoon session carrying no formal GOP budget proposal, but he is laden with the promises he made to far-right and other conservative Republican lawmakers during his difficult campaign to become House speaker. He vowed then to work to return federal spending to 2022 levels — an 8% reduction. He also promised to take steps to balance the budget within the decade — an ambitious, if politically unattainable goal.

McCarthy said he told the president, "I would like to see if we can come to an agreement long before the deadline.”

The political and economic stakes were high for both leaders, who have a cordial relationship, and for the nation as they worked to prevent a debt default. But it was doubtful that this first meeting since the embattled McCarthy won the speaker's gavel would yield quick results.

U.S. & World

The day's top national and international news.

“Everyone is asking the same question of Speaker McCarthy: Show us your plan. Where is your plan, Republicans?” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., ahead of the afternoon meeting.

"For days, Speaker McCarthy has heralded this sitdown as some kind of major win in his debt ceiling talks," Schumer said. But he added, “Speaker McCarthy showing up at the White House without a plan is like sitting down at the table without cards in your hand.”

The nation is heading toward a fiscal showdown over raising the debt ceiling, a once-routine vote in Congress that has taken on oversized significance over the past decade as the nation's debt toll mounts. Newly empowered in the majority, House Republicans want to force Biden and Senate Democrats into budget cuts as part of a deal to raise the limit.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen notified Congress last month that the government was reaching the limit of its borrowing capacity, $31 trillion, with congressional approval needed to raise the ceiling to allow more debt to pay off the nation's already accrued bills. While Yellen was able to launch “extraordinary measures” to cover the bills temporarily, that funding is to run out in June.

Ahead of the White House meeting, House Republicans met in private early Wednesday to discuss policies. McCarthy met with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell on Tuesday at the Capitol.

McConnell has a history of dealmaking with Biden during the last debt ceiling showdown a decade ago. But the GOP leader of the Senate, in the minority party, says it's up to McCarthy and the president to come up with a deal that would be acceptable to the new House majority.

Still, McConnell is doing his part to influence the process from afar, and nudging Biden to negotiate.

“The president of the United States does not get to walk away from the table,” McConnell said in Senate remarks. “The American people changed control of the House because the voters wanted to constrain Democrats’ runaway, reckless, party-line spending.”

Slashing the federal budget is often easier said than done, as past budget deals have shown.

After a 2011 debt ceiling standoff during the Obama era, Republicans and Democrats agreed to across-the-board federal budget caps on domestic and defense spending that were supposed to be in place for 10 years but ultimately proved too much to bear.

After initial cuts, both parties agreed in subsequent years to alter the budget caps to protect priority programs. The caps recently expired anyway, and last year Congress agreed to a $1.7 trillion federal spending bill that sparked new outrage among fiscal hawks.

McCarthy said over the weekend he would not be proposing any reductions to the Social Security and Medicare programs that are primarily for older Americans, but other Republicans want cuts to those as part of overall belt-tightening.

Such mainstay programs, along with the Medicaid health care system, make up the bulk of federal spending and are politically difficult to cut, particularly with a growing population of those in need of services in congressional districts nationwide.

After Wednesday morning's closed-door House GOP briefing, several Republican lawmakers insisted they would not allow the negotiations to spiral into a debt crisis.

“Obviously, we don’t want to default on our debt. We’re not going to,” said Rep. Warren Davidson, R-Ohio. “But we are going to have to have a discussion about the trajectory that we're on. Everyone knows that it’s not sustainable.”

Rep. Kevin Hern of Oklahoma, chairman of the Republican Study Committee, held a separate briefing for his group, whose 175 or so members make up most of the House GOP majority.

Hern sent a letter to McCarthy outlining their principles for budget cuts ahead of the White House meeting.

“We’re not out here trying to not pay our debts,” Hern said. “But it’s also a time of reflection of how we change this direction.”

The federal budget's non-mandatory programs, in defense and domestic accounts, have also proven tough to trim.

Agreeing on the size and scope of the GOP's proposed cuts will be a tall order for McCarthy as he struggles to build consensus within his House Republican majority and bridge the divide between his conservative and far-right wings of the party.

Biden has been here before, having brokered 2011-12 fiscal deals when he was vice president with McConnell.