Summer Boismier at the Brooklyn Public Library’s main branch. Boismier, a former Oklahoma school teacher, is fighting efforts to ban books.

When a wave of book bans began sweeping the country, the Brooklyn Public Library fought back. It made the titles available online to students everywhere. Since April, its Books Unbanned program has gotten 6,000 requests for digital library cards from teenagers in all 50 states.

Now the library is teaming up with PEN America, a nonprofit organization focused on free expression in literature, to bring the battle over censorship to the students’ hometowns. A new series of virtual sessions, the Freedom to Read Advocacy Institute, will teach teenagers how to defend the books in their schools, libraries and communities.

Among the panelists will be activists like Jack Petocz, an 18-year-old student at Flagler-Palm Coast High School in Florida, who fought the removal of George M. Johnson’s "All Boys Aren’t Blue" from his school district’s libraries. Many of the targeted books are, like "All Boys Aren't Blue," about the LGBTQ communities and race and racism.

"In one of the darkest blips of Florida, I made a difference," said Petocz, a mobilization coordinator for Gen-Z for Change. "They can as well."

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

On the agenda: the history of book bans, the rights they have as students, how the First Amendment applies to school libraries and the actions they can take. They will hear from Ashley Hope Perez, the author of one of the most often targeted titles, “Out of Darkness," Reshama Sanjuani, founder of Girls Who Code, and Jen Cousins, the co-founder of the Florida Freedom to Read Project.

The Freedom to Read Advocacy Institute

What: A free, online series open to high school students across the country. Join the waitlist here

When: Four Thursdays in February beginning Feb. 2

Why: To teach students how to combat censorship in their schools and libraries

Summer Boismier, a former Oklahoma high school English teacher, helped to develop the session on opposing what are frequently orchestrated campaigns to remove books. Boismier, who now works at the Brooklyn Public Library, wants to show students how to use school policies to their advantage.

"They know this is wrong," she said. "But they don’t always know how to push back, how, for example, to effectively engage with your school board, where to find the information that you need to do that, how to access school policies around challenged materials, libraries and classroom libraries."

At the beginning of the current school year, Boismier said she was told to cover up the books in her classroom library in the Norman, Oklahoma, public schools after the state passed a law regulating what could be taught about race and sex. She complied but added these words, “Books the State Doesn’t Want You to Read,” and included the QR code to the Brooklyn Public Library’s Books Unbanned web site. She was suspended after nearly a decade of teaching and then resigned.

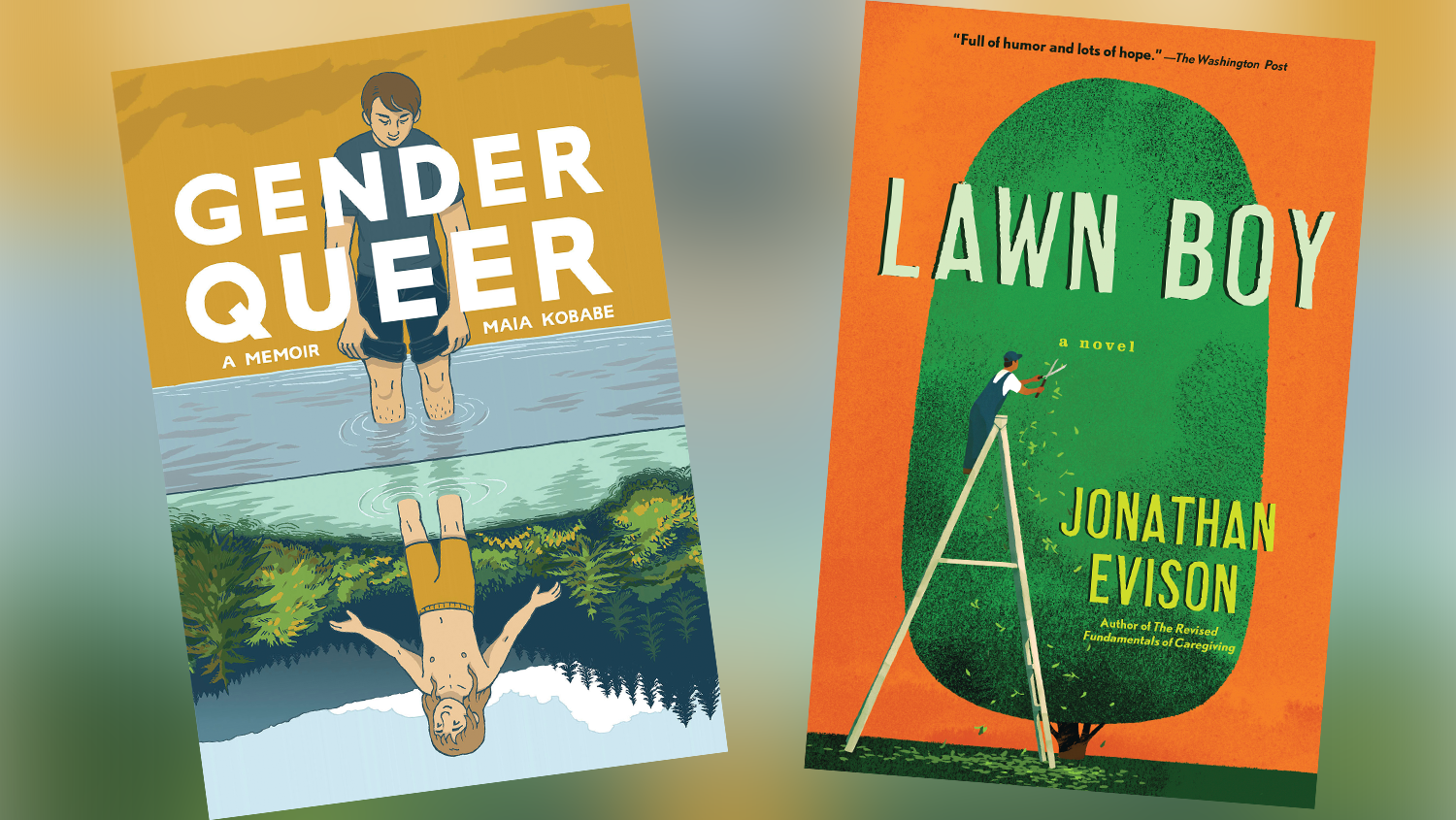

According to the American Library Association, the five most frequently challenged books in 2021 were Maia Kobabe's "Gender Queer," "Lawn Boy" by Jonathan Evison, “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “Out of Darkness” and "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas. All tackle LGBTQ topics or issues of race and racism.

“This is really about lives, whose lives get to count, and which identities are quote, unquote acceptable,” Boismier said.

“Laws like what Oklahoma has on the books, laws like Florida is currently going viral for, they treat every student with a book as inherently suspicious.”

At the Brooklyn Public Library, librarian Karen Keys works with teenagers and young adults who told the library that they needed help in fighting book bans. They want to know how to sign up to speak at a school board meeting, how to prepare a speech, how to write letters to the editor and how to get the word out to their fellow students, she said.

“More than anything they just want to understand why this happens and what the motivations for it are," Keys said.

What she became a librarian in 2007, she was not as worried about challenges to books even as libraries drew attention to censorship during Banned Books Week.

"It didn't have the same force," she said. "It didn't feel as important. It was just a way to send the message, 'You have the right to read whatever you want to read.' It didn't feel as tied to current events and what was going on. There have always been book bans and book challenges but it's just at an unprecedented rate right now."

The Freedom to Read Advocacy Institute is meant to prepare teens to be warriors in the fight against book challenges,” Keys said. The hope is to have a cohort of free expression advocates to combat book banning.

“This isn’t entirely about the books,” Keys said. “It’s about attacking people you don’t agree with.”

Also in the News

În September, PEN America released a report showing that during the previous school year, 1,648 books in more than 5,000 schools were banned, more than in any previous year. Texas banned more books that any other state with 801 titles, followed by Florida with 566.

Of the books, 41% had LGBTQ themes or main characters, while 40% featured main characters of color.

The recent attempts to censor books are often led by conservative advocacy groups. What began as modest school-level efforts remove books at the start of the 2021-2022 school year became a full-fledged social and political movement originated by not only local groups by also by state and national ones, according to PEN. It has identified at least 50 groups involved in books bans.

Parents who have challenged books argue that schools should value their opinions. They say they are preserving their parental rights over what their children read and should have a say in what their children are taught.

They call some of the books pornographic or obscene and say they cover topics not suitable for the children's ages. The books present radical ideologies inappropriate for their schools that indoctrinate students in viewpoints at odds with the country, they say.

“We all can agree that parents deserve to and are entitled to a say over their kids’ education,” Suzanne Nossel, the head of PEN America, said in September. “That’s absolutely essential. But fundamentally, that is not what this is about when parents are mobilized in an orchestrated campaign to intimidate teachers and librarians to dictate that certain books be pulled off shelves even before they’ve been read or reviewed."

Petocz, who was the honoree for the 2022 PEN/Benenson Courage Award, was suspended from school in March after organizing a statewide student walk-out in protest of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law. That law dictates how public school teachers address gender identify or sexual orientation in classrooms. Instruction may not occur in kindergarten through the third grade or in a way that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.

As he fought for "All Boys Aren't Blue" to remain available in his district, "My friends and I were met with name-calling, insults from government officials, and threats from individuals belonging to hate groups," he said. "In the end, this resistance just made our comradery and pursuit to fight stronger. It revealed those who truly support this kind of book banning."

Jonathan Friedman, who directs PEN America’s free expression and education programs, said the first Freedom to Read Advocacy Institute was intended as a pilot program with the potential to develop additional ones.

“I think that the fight for public education is becoming a fight that many young people are eager and hungry to engage in, particularly as the spread censorship is reaching further into their lives," he said.

Also in the News

The current wave of censorship is more significant than past ones, partly because of the publicity afforded by the internet and partly by the number of politicians participating in efforts to ban books. The effort is frequently partisan.

In Texas, for example, former Republican state Rep. Matt Krause produced a list of 850 titles dealing with racism or sexuality that could “make students feel discomfort." He wanted schools districts in the state to determine whether the books were in their libraries.

League City, outside of Houston, created a "community standards review committee" to review challenged books and decide if they should be restricted from minors or removed from the city's library.

Florida now requires a certified media specialist to approve of all books available in school classrooms and threatens teachers with felony violations.

"You have people in elected positions who are basically using those positions to control and determine the availability of information for everybody," Friedman said.