In the 1930s, as Hitler rose to power, tens of thousands of Jewish people fled Germany, and 13-year-old Eva Black was one of them. She escaped to the United States with few possessions, but one — her grandfather’s violin — would shape the course of her life.

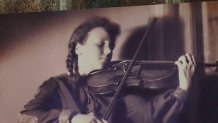

Eva Black would go on to become an accomplished classical violinist, performing with the National Symphony Orchestra in D.C.

"She cherished both the original case and the instrument her whole life," said her son, Dean Black, himself a fifth-generation musician, who was raised in D.C. and now lives in South Carolina.

Dean Black has kept the violin since his mother’s death. Now 200 years old, the violin originally belonged to his great-grandfather, Franz Landsberger.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

In 1901, Landsberger helped open the Beuthen City Opera House in Germany, raising money to build the grand theater by playing that violin. When the Nazis came to power, they removed the plaque honoring Landsberger’s contribution to the opera house because he was Jewish.

The opera house itself was renamed, as was the town. Generations passed, the borders changed and the opera house’s connection to the Black family and that violin became a faded memory — until last summer.

'I felt it was my destiny that I ended up with this violin and how important it was'

Just holding the violin brings Dean Black closer to his family roots.

"Well, some pretty deep emotions. Knowing that my mom held and played this instrument many times, knowing that my grandfather played this instrument, knowing that my great-grandfather played it quite often, and actually played it to help raise money to get that theater built, you can't help but just to feel a special connection to your relatives," he said.

That connection continues. Last summer, officials in Landsberger’s town — now Bytom, Poland — decided to rededicate the opera house and restore the plaque honoring him.

Town officials tracked down more than 40 of Landsbergers' descendants from around the world and invited them to the rededication ceremony.

Dean Black not only made the trip — he brought his great grandfather’s violin back home, and with it, his mother’s memory.

"I felt it was my destiny that I ended up with this violin and how important it was to refurbish it and carry it and make sure it made it to the event, so it was really earth-shattering," he said.

Dean Black carried the violin in a backpack case through Budapest, Hungary, on a train to Vienna, Austria, and then over to what is now Bytom, Poland.

This past June, for the first time in nearly 100 years, the violin that helped build a grand theater, an instrument that had survived the Holocaust and traveled halfway around the world, was back home. There, it once again filled the opera house it helped to build with its glorious tones.

"When I first heard it played in the theater, it really brought tears to my eyes, and even just holding the instrument, I really feel like my mom and my grandfather and great-grandfather would be really proud of what we've done with the violin," Dean Black said.

"And knowing that this violin hadn't been in that theater for a hundred years, you know, it brought me to tears," he said. "What can I say? I cried. It was that meaningful."

Dean Black said he is considering loaning the violin to the opera house for a temporary display. But he's concerned about the possibility Russia could invade Poland, plunging the violin once again into the middle of a war zone.