These are the faces of people who lost their lives to COVID-19: parents, pastors, doctors, teachers, firefighters — people from every age group and all walks of life.

Monday marks four years since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic. Almost 1.2 million people in the U.S. have lost their lives to the virus.

For many families, the pandemic wounds are still raw, four years later.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

"We need to acknowledge COVID. We lost over a million people," said Anne Starkweather. Her husband, Chad Capule, was one of them.

He died in March 2020, and four years on, she's still processing the grief and trauma.

"It still makes me sick to this day that he's not here. I will never be the same," she said.

Local

Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia local news, events and information

Capule, an IT manager from Cheverly, Maryland, got sick while traveling to a Wisconsin hospital to set up their new computer system. Three weeks later, he died there, alone in the ICU.

His wife and sisters never got the chance to say goodbye in person.

"I feel robbed and a bit angry and jealous that we could not do that," said one of his sisters, Angie Fontanilla.

His wife told us: "That breaks my heart whenever I think about it. Him being there alone and dying alone, with no one to hold his hand, no one to tell him it was OK."

'They could not be with their loved ones as they lay dying'

It's a sentiment echoed by so many who weren't allowed inside hospitals and were forced to hold funerals virtually, for fear of spreading the virus.

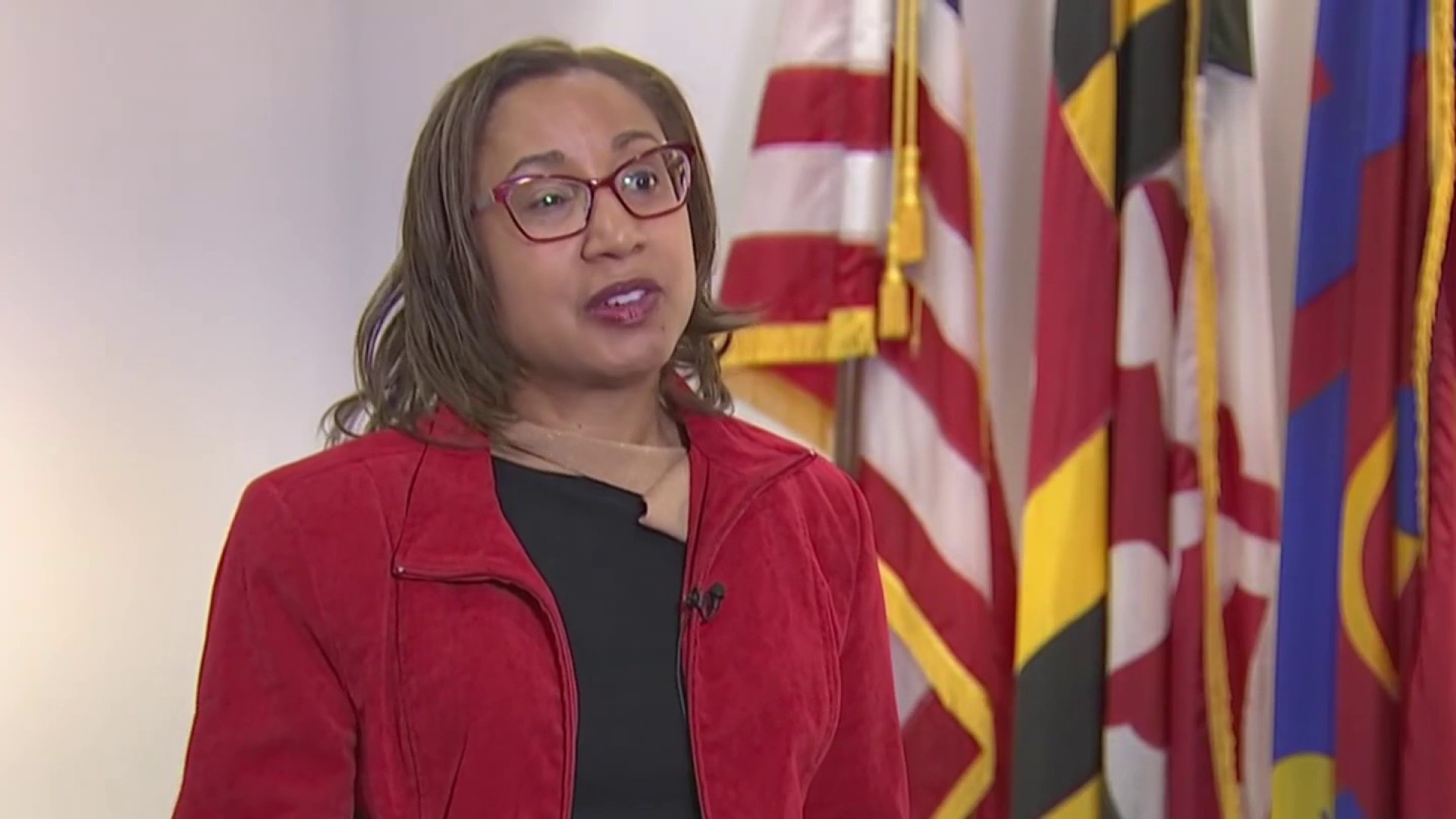

"That uncertainty translated into isolation, that they could not be with their loved one as they lay dying," said Sarah Wagner, an anthropology professor at The George Washington University. "They couldn't be there to hold a hand, to press a cheek. They couldn't say those words, a final goodbye. Or if they did, they had to do so mediated by technology."

"Often people are left in the very space where their loved one had sat next to them," Wagner said. "Same bed, same room, same kitchen. They're not there, but they're also not able to bring in family and friends to kind of get through that period."

Wagner and and fellow GW anthropology professor Roy Richard Grinker are members of a research team called Rituals in the Making, which is focused on COVID death, mourning and memorialization.

Over the past four years, they’ve found that silence about COVID hurts people who are still grieving.

"When there is this enveloping silence around 1,200,000 deaths, and we don't talk about it — that silence doesn't make it easier for the people who are grieving, right? … This mourning process is truncated," Wagner said. "The grief is being compounded."

Temporary displays could inspire a more permanent memorial

To honor the victims and acknowledge the grief, memorials have popped up, both big and small, including a powerful public art installation outside RFK Stadium in fall 2020, and another on the National Mall the following year displaying thousands of personalized flags.

Those temporary memorials provided safe places for people to mourn and the nation to reflect.

"I was on the mall with all the flags in the wind and the sun and all these people everywhere," Grinker recalled. "And I said, 'What would a support group look like for you to help you mourn the loss of your loved one?' And she looked around and said, 'This. This is a support group for that.'"

Suzanne Firstenberg is the artist behind the moving displays titled "In America: Remember," capturing a sobering snapshot in time.

"That's one of the things about grief in America," she said. 'We have no idea who's grieving near us. One in three people experienced a COVID death of a relative, a friend, a coworker."

Fontanilla told us: "It was helpful for us, for me, in the healing process to see that we were not alone."

"So It felt like a sense of community with these other people that had also suffered," Starkweather said.

"So you had people who came and they, for the first time, felt as if, through that installation, that their loss was being recognized," Wagner said.

"It felt like the funeral they never had, or that was like a proxy gravesite that they could go to," she said.

And the work isn't over.

Firstenberg still has the 20,000 personalized flags from the 'In America' exhibition. She's working with the team at GW on the painstaking task of archiving every single one and creating a database that researchers and relatives will be able to access.

For mourners, it's a start, with an end goal of someday having a more permanent memorial for future generations to remember.

"9/11 changed the country. COVID changed the country," Fontanilla said. "It would be good to have something that people can go to, and to remember that, and to tell future generations that, 'Hey, [this is] something important and something to learn from.'"

Firstenberg has blank white flags at her Bethesda art studio, where people can go to fill them out and honor loved ones who died of COVID-19. She says any new flags will be archived and saved into the database they're building.