A handful of super powerful tropical storms in the last decade and the prospect of more to come has a couple of experts proposing a new category of whopper hurricanes: Category 6.

Studies have shown that the strongest tropical storms are getting more intense because of climate change. So the traditional five-category Saffir-Simpson scale, developed more than 50 years ago, may not show the true power of the most muscular storms, two climate scientists suggest in a Monday study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They propose a sixth category for storms with winds that exceed 192 miles per hour (309 kilometers per hour).

Currently, storms with winds of 157 mph (252 kilometers per hour) or higher are Category 5. The study's authors said that open-ended grouping doesn't warn people enough about the higher dangers from monstrous storms that flirt with 200 mph (322 kph) or higher.

Several experts told The Associated Press they don't think another category is necessary. They said it could even give the wrong signal to the public because it's based on wind speed, while water is by far the deadliest killer in hurricanes.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up here.

Since 2013, five storms — all in the Pacific — had winds of 192 mph or higher that would have put them in the new category, with two hitting the Philippines. As the world warms, conditions grow more ripe for such whopper storms, including in the Gulf of Mexico, where many storms that hit the United States get stronger, the study authors said.

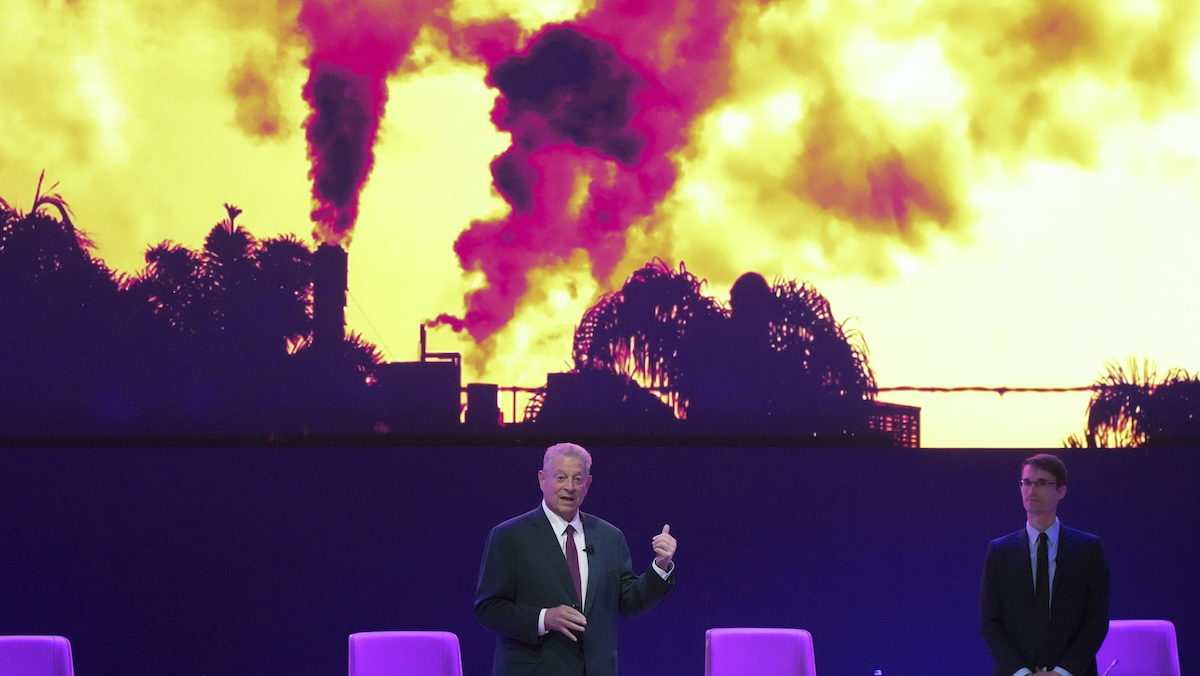

“Climate change is making the worst storms worse," said study lead author Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at the Lawrence Berkley National Lab.

It's not that there are more storms because of climate change. But the strongest are more intense. The proportion of major hurricanes among all storms is increasing and it's because of warmer oceans, said University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy, who wasn't part of the research.

Changing Climate

News4 is Working 4 You with in-depth coverage of our changing climate. Learn how it impacts your family, your money, your health and your commute.

From time to time, experts have proposed a Category 6, especially since Typhoon Haiyan reached 195 mph wind speeds (315 kilometers per hour) over the open Pacific. But Haiyan "does not appear to be an isolated case,” the study said.

Storms of sufficient wind speed are called hurricanes if they form east of the international dateline, and typhoons if they form to the west of the line. They're known as cyclones in the Indian Ocean and Australia.

The five storms that hit 192 mph winds or more are:

— 2013's Haiyan, which killed more than 6,300 people in the Philippines.

— 2015's Hurricane Patricia, which hit 215 mph (346 kph) before weakening and hitting Jalisco, Mexico.

— 2016's Typhoon Meranti, which reached 195 mph before skirting the Philippines and Taiwan and making landfall in China.

— 2020's Typhoon Goni, which reached 195 mph before killing dozens in the Philippines as a weaker storm.

— 2021's Typhoon Surigae, which also reached 195 mph before weakening and skirting several parts of Asia and Russia.

If the world sticks with just five storm categories “as these storms get stronger and stronger it will more and more underestimate the potential risk,” said study co-author Jim Kossin, a former NOAA climate and hurricane researcher now with First Street Foundation.

Pacific storms are stronger because there's less land to weaken them and more room for storms to grow more intense, unlike the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, Kossin said.

So far no Atlantic storm has reached the 192 mph potential threshold, but as the world warms more the environment for such a storm grows more conducive, Kossin and Wehner said.

Wehner said that as temperatures rise, the number of days with conditions ripe for potential Category 6 storms in the Gulf of Mexico will grow. Now it's about 10 days a year where the environment could be right for a Category 6, but that could go up to a month if the globe heats to 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. That would make an Atlantic Category 6 much more likely.

MIT hurricane expert Kerry Emanuel said Wehner and Kossin “make a strong case for changing the scale,” but said it's unlikely to happen because authorities know most hurricane damage comes from storm surge and other flooding.

Jamie Rhome, deputy director of the National Hurricane Center, said when warning people about storms his office tries “to steer the focus toward the individual hazards, which include storm surge, wind, rainfall, tornadoes and rip currents, instead of the particular category of the storm, which only provides information about the hazard from wind. Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale already captures ‘catastrophic damage’ from wind so it's not clear there would be a need for another category even if the storms were to get stronger.”

McNoldy, former Federal Emergency Management Agency Director Craig Fugate, and University of Albany atmospheric sciences professor Kristen Corbosiero all say they don’t see the necessity for a sixth and stronger storm category.

“Perhaps I'll change my tune when a rapidly intensifying storm in the Gulf achieves a Category 6,” Corbosiero said in an email.