This winter has been the fourth warmest winter on record, and unfortunately for those with seasonal allergies, that means allergy season is starting already in the District.

Our changing climate means the allergy report for Thursday measured tree pollen at high levels. Grasses and mold spores were registering at low levels, even in mid-February.

According to microbiologist Susan Kosisky with the U.S. Army Allergen Extract Lab, weather conditions at the beginning of the year -- primarily temperatures -- strongly influence when trees start to release their pollen.

That can happen as early as mid-January, as we're seeing this year. 2023 saw the earliest spike in tree pollen on record, on February 9.

That's bad news for the 25 million Americans the CDC estimates have seasonal allergies.

Climate change is playing a role in the changing allergy season. As temperatures continue to warm, the growing season for plants is lengthening.

A longer growing season means a longer allergy season. With a growing season about 20 days longer compared to years past, according to nonprofit Climate Central, allergy sufferers may be sneezing earlier in the year.

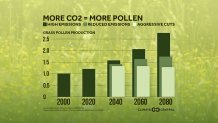

Allergy seasons are also more intense than they used to be. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere continue to increase, and since CO2 stimulates plant growth, there's more pollen in the air.

In the District, tree pollen typically peaks during the third or fourth week of April, making for a long allergy season ahead of us.