When Lauren Grom met her best friend, Julie Wood, she didn't know her friend would save her life one day.

Grom, an Arlington, Virginia, resident, met Wood six years ago at work for a property management company. They enjoyed traveling and going hiking together.

In 2020, Grom learned from her doctors at D.C.'s George Washington University Hospital that she would have to either start dialysis or begin the long process of trying to find a kidney donor. She was just 36 years old at the time.

Wood, who is now 36, was worried about her friend and also, she confessed, the life they shared as friends.

We've got the news you need to know to start your day. Sign up for the First & 4Most morning newsletter — delivered to your inbox daily. >Sign up here.

“The thought of her going on dialysis wasn’t an option for me,” Wood said. “I kind of selfishly was like, 'She’s going to have to be doing this a few times a week. What about our little hiking adventures together?'"

Wood decided to look into whether she could help as a kidney donor. There were no guarantees. Siblings won't necessarily be a match, according to the National Kidney Foundation. A parent and child have only a 50% chance of being a match. Unrelated donors are even less likely to match.

Wood went to MedStar Georgetown University Hospital for testing, and she and Grom were stunned to learn they were a match.

"Julie was the first person tested, and she was a direct match," Grom said. "In the words of one of the doctors at Georgetown: It’s a miracle. It was such a life-changing experience. Honestly, I don’t know how to be sad anymore."

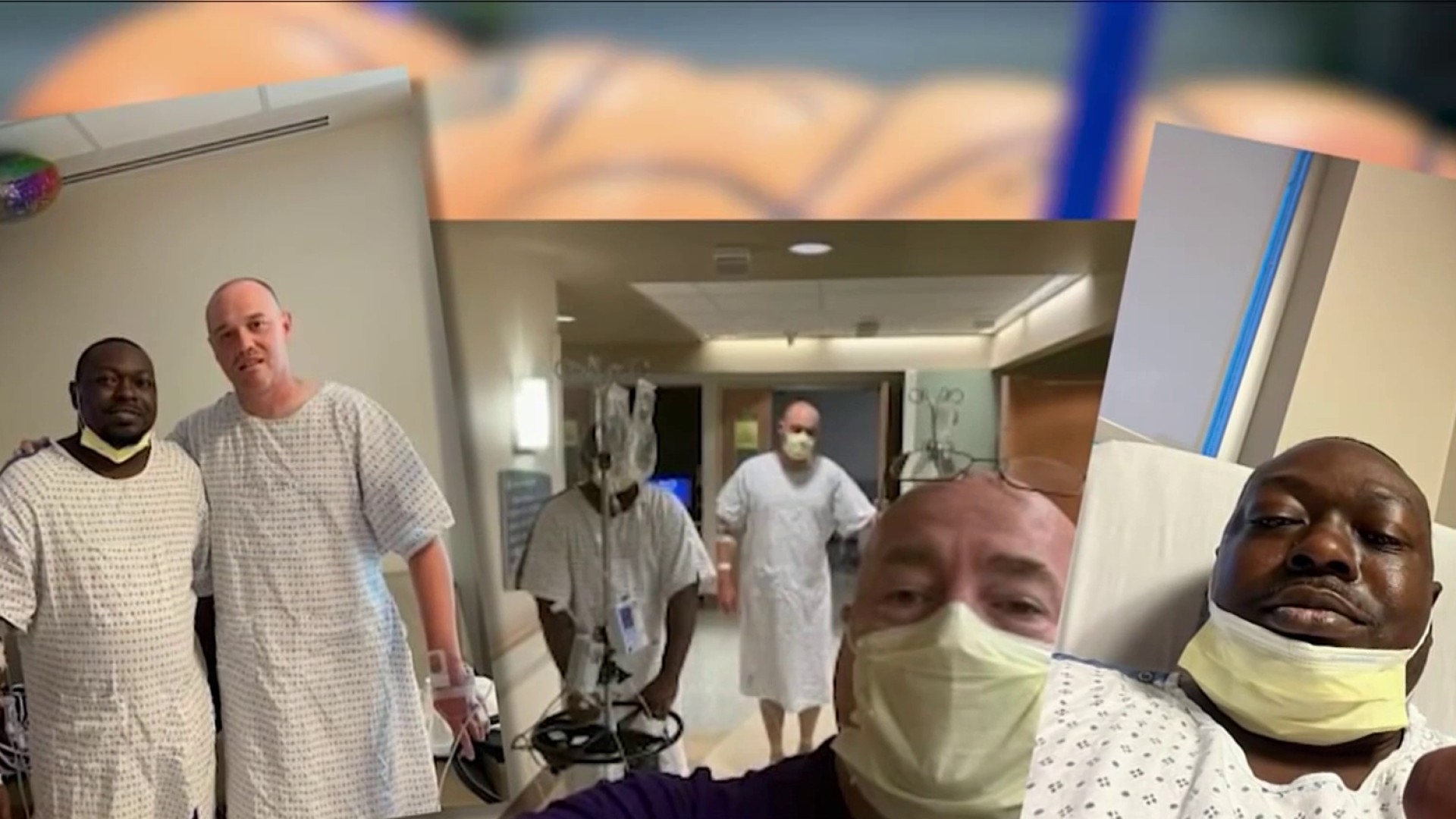

Grom had the kidney transplant operation and spent three days in the hospital. Both she and Wood needed three weeks to recover before they could return to work.

They shared their story with News4 at the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital Transplant Institute’s Donor Appreciation Night last month.

Wood said she and Grom are now bonded for life.

“There was not any doubt that we had met almost to be able to do that,” she said.

'The greatest gift that one person can give to another'

Dr. Jennifer Verbesey, an expert in kidney/pancreas transplants for adults and children, is the director of the Living Donor Kidney Transplant Program at the MedStar Georgetown Transplant Institute. She pointed out that the patient waiting list for kidneys far exceeds the available supply.

Over 100,000 people in the U.S. are currently awaiting a kidney transplant, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Verbesey urged people to check their donor status on their driver's licenses and consider becoming living donors.

“We love living donors because people can donate one of their kidneys, which work faster and last longer. It is the greatest gift that one person can give to another,” she said.

Donated kidneys don’t last forever, and one difference between a kidney from a deceased donor and a living one is that kidneys from living donors tend to last longer in recipients.

In the D.C. area, people wait an average of five to eight years for a kidney transplant after starting dialysis, Verbesey said. While dialysis helps people stay alive, it can be a difficult way to live.

“At least three days a week, you must get hooked up to a machine for four to five hours. It’s hard to work, It’s hard to travel. It’s hard to do anything that makes life enjoyable,” Verbesey said.

Verbesey flagged a big misconception: that people need to find a perfect match to get an organ donation or donate. The National Kidney Registry’s Voucher program allows people to donate a kidney without a specific recipient.

“We can swap and exchange all the donors and recipients who come in, if they’re incompatible. So, any donor is a great donor,” Verbesey said.

A voucher lets the donor list up to five family members, ensuring they will get the kidney if they ever need a transplant.

According to the United States Renal Systems (USRDS), in 2021, the incidence of end-stage renal disease among Black individuals was 3.9 times that of white individuals. The incidence among Native American individuals was 2.3 times as high. It was twice as high among Hispanics. These disparities improved until 2018 and worsened from 2018 to 2021.

The USRDS annual report says that in 2021, about 121,972 Americans were diagnosed with end-stage renal disease, meaning they need dialysis or a transplant to survive. That year saw only 25,549 transplants. The remaining people had to rely on dialysis.

Bill proposes $50,000 tax break for kidney donors

The End Kidney Deaths Act was created by a group of experts and living donors. The bill proposes that every non-directed donor, meaning someone who donates their kidney to a stranger rather than a family member, be eligible for a refundable tax credit of $50,000 allocated over the first five years after donation. That’s according to Elaine Perlman, executive director of Waitlist Zero.

Perlman donated her kidney to a stranger about four years ago. Now, she leads the Coalition to Modify NOTA (the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984). Perlman says the incentive would motivate more Americans to become donors.

“With this incentive, we will grow the number of people giving kidneys to strangers in the U.S.," Perlman said. “From the current 400 [donors] annually, it will grow to 6,000 annually. By the 10-year mark, we’ll be able to save 60,000 American lives."

Perlman said that taxpayers save about a half-million dollars each time a patient is moved from dialysis to transplantation. Due to a law signed by Richard Nixon, Medicare picks up the bill for most patients with kidney failure, including expensive dialysis treatments.

Perlman said she believes in incentivizing and recognizing kidney donation.

“Donation is work. It involves time, stress and pain. It's a difficult experience but it's gratifying. I would do it again if I could, but it is something that is unpaid work at this time," she said.

One objection to compensating kidney donors is the idea that it lets people sell their kidneys. The End Kidney Deaths Act does not seek to legalize the selling of organs, Perlman said. Rich people would not be able to outbid poorer people to get organs first. The proposal is to pay donors for their labor, not pay them for an asset.

Work to pass the bill began in January after a 10-year pilot program. While advocates say they still have a long way to go, they are hopeful the bill will be passed and can save lives and taxpayer funds.

To learn about potentially becoming a kidney donor, visit the National Kidney Registry or MedStar Health’s organ donation page.