- The federal government provided states with nearly $24 billion in stabilization funds to keep child care services afloat as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

- However, more than 70,000 child care providers who benefited are likely to close after the program expires this month, shutting down care for 3.2 million kids, a think tank estimates.

- Experts say that systemic change, such as broader parental leave and more public funding for child care, must be involved for child care to improve at a larger scale.

Child care is already scarce and expensive — and the stakes are about to get higher.

The federal government provided states with nearly $24 billion in stabilization funds to keep child care services afloat as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021.

That program expires at the end of this month.

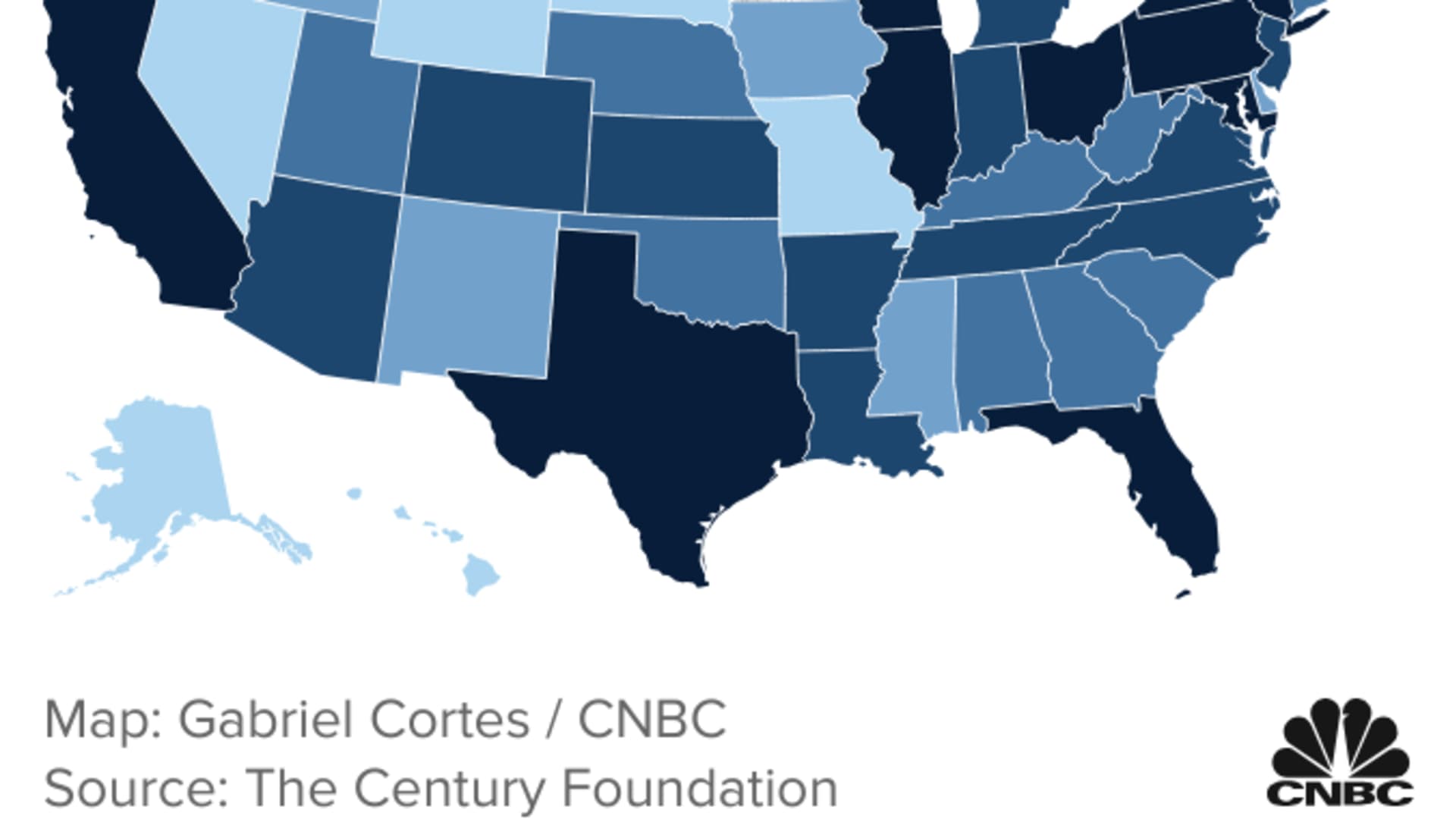

More than 70,000 child care providers who benefited are likely to close as a result of lost funding, according to estimates from The Century Foundation, a liberal think tank. That would affect 3.2 million kids and slash $10.6 billion in revenue from lost worker productivity as parents reduce hours or leave jobs in the scramble to find new care.

More from Personal Finance:

Money market funds vs. high-yield savings accounts

Women will accept much lower salaries than men

Homeowners say 5% is the magic number to move

Researchers came to these figures based on data from a survey of 12,000 early childhood educators from all states and settings — including faith-based programs, home providers, Head Start programs and child care centers — as well as data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Care.

"Quality, affordable child care is already scarce, and the child care workforce is already badly underpaid and under great stress," said Lauren Hipp, national director for early learning at advocacy group MomsRising. "As pandemic child care relief runs out, all that is likely to get worse."

The share of working mothers with young children is at historic levels, exceeding other working-age women's labor participation growth from 2020, The Hamilton Project found. However, experts are concerned that this loss of child care options will pull more people, especially women, back out of the workforce.

Money Report

Child care 'is a public good'

Experts say that systemic change, such as broader parental leave and more public funding for child care, must be involved for child care to improve at a larger scale.

Child care "is a public good just as much as having clean water, having a strong education system, having access to health care," said Hipp. "The access to child care has an immediate impact on everyone in society."

Child care providers want to be able to support families but can't make it work on the amount they make, she added. The hourly wage of a child care worker in 2022 was $13.71 per hour or $28,520 annually, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

"If you work in a preschool private child care center versus a kindergarten classroom, that wage differential is huge," said Taryn Morrissey, a public policy professor at American University. "The wage difference is quite large because the K-through-12 education sector has public financing."

Teachers in elementary, middle and high schools generally make higher salaries. While kindergarten and elementary school teachers roughly earned $61,620 last year, high school teachers made $62,360, the U.S. Department of Labor has found.

Plus, teachers enjoy an array of benefits, such as health insurance and retirement plans, while oftentimes early care and education workers do not, she added.

Moreover, parents often deal with early child care costs when they are at the lowest earning years of their careers, without low-interest loans or subsidies to lean on, said Morrissey.

The national annual cost of child care was about $10,853 for one child in 2022, the organization Child Care Aware of America found. In 2023, 67% of parents reported spending 20% or more of their household income on child care, Care.com found.

"If you have two kids under 5, in most parts of the country, you're really struggling," Washington, D.C.-based Morrissey added.

While child care issues financially affect women in particular in both the short term and long term — including in a loss in wages and retirement savings — the economy also takes a hit. When parents don't have access to affordable, reliable child care, the U.S. loses about $122 billion a year in economic productivity and revenue, according to a report from Council for a Strong America.

"All of these factors mean that it impacts and is important to people who do or do not have children," said Hipp.

Use the benefits you have available

Your workplace may have some options to help you find care, such as backup care providers or on-site child care. Other companies offer benefits to help finance child care costs. Some companies provide employees with a dependent-care flexible spending account, or FSA, allowing households to set aside up to $5,000 in pretax dollars from a paycheck.

If you are expecting, you may have access to workplace and state programs for paid leave that can give you and your partner time at home, stretching your time to find a caregiver.

Workplace benefits, including parental leave, may be a resource for many workers. In 2022, 35% of organizations offered employees paid maternity leave, according to the Society for Human Resource Management, and 27% have paid paternity leave. Those figures are down from 2020 rates of 53% and 44%, respectively.

Outside of workplace benefits, 13 states and the District of Columbia offer paid family leave for workers, said Katherine Gallagher Robbins, senior fellow of The National Partnership for Women and Families. Those states are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington.

"Make sure you are taking advantage of the policies that you do have in place and where they do exist," she added.

Cast a wide net for care

With fewer child care providers available, families might need to get creative and consider different options in their area, experts say. That might include talking with other parents about starting a child care co-op or sharing a nanny.

Some states and cities offer universal preschool programs where kids can enroll into the public education system before the age of 5, added Morrissey.

Washington, D.C., and six states have implemented universal preschool, such as Florida, Iowa, Oklahoma, Vermont, West Virginia and Wisconsin, the National Institute for Early Education Research found. Washington, D.C., is the only jurisdiction to provide universal preschool at ages 3 and 4, the institute notes.

Georgia, Illinois, Maine and New York have universal preschool policies but have yet to put them in practice. Meanwhile, California, Colorado, Hawaii and New Mexico passed laws to provide universal preschool in the past year.

Also consider signing up on waitlists at child care centers early, experts say. While putting your child on the waitlist oftentimes does not guarantee a spot, it is a line of security worth having.

Lean on your community

Additionally, think about ways you can lean on your community or support system to help care for your child, experts say.

Some families are asking for care help from friends and family members, or even relocating to be closer to family. Others are working multiple jobs or adjusting their work schedules, according to Care.com.

"There's a reason that there's a proverb 'it takes a village to raise a child,'" said Hipp.

Correction: A report from Council for a Strong America concluded that the U.S. loses about $122 billion a year when parents don't have access to affordable, reliable child care. Incorrect information appeared in an earlier version of this story.