D.C. firefighter Myisha Richards always considered herself one of “the good guys,” but as she continues to recover from a brutal assault, which she said came at the hands of a patient who called for help, she admitted, “I feel like a lot of things changed.”

Richards and her partner were responding to a call for someone having trouble breathing. Minutes later, Richards was the one who needed help, she said.

Shortly after arriving at the Southwest D.C. apartment the afternoon of July 31, 2020, the people inside starting fighting, Richards said. She and her partner decided to leave, but before they could reach the stairs and call for police backup, Richards was attacked, she said.

“The girl jumped over the railing and she came down and just started, like, wailing on me, basically," she said. "Then the other girl came down, the (trouble breathing) patient that we were there for. They literally beat me for two minutes.”

Richards said the last things she remembers were radioing for help and seeing one of the women’s shoes kicking her face.

When she got to the hospital, she needed stiches above her eye, had bruises on her face, a concussion and was missing hair where she said the attackers pulled handfuls from her head.

Local

Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia local news, events and information

When questioned by police, one of the women told officers, “They were in a fight with the EMS personnel because they were unhappy with their services,” court records obtained by the News4 I-Team show.

Court records show the two women were arrested, but charges against one were dropped. The other was sentenced to more than 60 hours of community service, according to records.

Richards said she is still dealing with the effects years later.

“We are the good guys,” Richards told the I-Team, adding, “I feel like a lot of things changed.”

The I-Team’s examination of violence firefighters and EMTs face on our streets comes as insiders suggest violent attacks are on the rise.

Just days ago, assault charges against two D.C. firefighters were dismissed. Those firefighters had been seen on video hitting someone on scene as other firefighters treated someone nearby. The firefighters always said that a bystander started the assault.

“I would say it's getting worse,” D.C. firefighters union President David Hoagland told the I-Team. Firefighters are getting hit “fairly often,” according to Hoagland, but official counts are hard to find.

After she was assaulted, Richards told the I-Team, “I just moved differently because I was always on a high alert." Eventually, she said, the PTSD from her assault kept building up inside. She got back to work, but withdrew, said she stopped seeing friends, drank far too much and one day on a medical call just couldn't do her job anymore.

"I just kind of froze,” Richards told the I-Team. “I could not really function other than the only thing I could worry about was what everybody else was doing and how we can get up out of there."

She finished her shift and checked herself in to a 45-day inpatient rehab in Maryland solely for firefighters dealing with addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder. The Center of Excellence is funded by the International Association of Firefighters for its members.

Now back at work, Richards is speaking out.

“I'm very vocal about talking about it because I'm not the only one, right," she said. "And I think that we all get in that position where we think that we're the only ones, and sometimes talking about it helps other people.”

Most departments don’t keep records, and Hoagland said many firefighters consider some assaults from patients as “part of the job.”

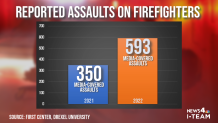

The FIRST Center at Drexel University tracks "media-covered" assaults on firefighters. In 2021, researchers scoured online reports of firefighters assaulted on duty and found 350 around the United States. A year later, in 2022, researchers found 593.

Jennifer Taylor, the center’s founding director, cautioned the I-Team the data only reports those assaults picked and reported by news organizations. She doesn’t dispute that firefighters are facing tough conditions on America’s streets.

“The first time someone assaults you, you're never going to forget it and you're never going to do the job the same," she said.

FEMA and the International Association of Firefighters help fund work at the FIRST Center solely studying firefighter injury and safety.

Taylor warns the nation’s EMS workforce is overworked and doesn’t have time to recover from either the PTSD of seeing traumatic situations or violent patients.

“We hung out a shingle that says, if you need something, call 911, but we didn't staff for it," she said. "We don't have enough EMS responders to respond to the 29 million calls we had for EMS last year and so we're doing the work on the back of this workforce, and they are not able to recover from the day-to-day stress of maybe going on 15, 20 runs for who knows what.”

Taylor and her team at the FIRST Center are developing training programs to deal with the emerging threat.

“There's nothing that trains a paramedic or an EMS responder in a fire department that the work may become violent until now," she said.

The center developed model SAVER policies for fire departments to adopt including:

- Allowing on-scene personnel to decide to leave an unsafe call with or without a patient.

- Mandating dispatchers share information about previously known violent locations.

- Dispatching police with fire and EMS to potentially dangerous calls.

- Increased violence reporting and sharing of that information within departments.

Experts told the I-Team addiction and untreated mental illness are fueling many of the assaults. They occur not just on calls for health emergencies, but even sometimes responding to a burning home.

The union that represents D.C. firefighters would like to see de-escalation training for its members.

Hoagland confirmed getting hit or kicked is considered part of the job as long as it isn't a serious injury.

“I think unfortunately it's moving in that direction, but we're realizing that that really needs to change,” he said.

D.C. Fire & EMS still offers all members professional counselors but has seen a 10-15% annual growth in the number of peer counselor visits.

“I think you need it now more than ever,” D.C. Fire & EMS Lt. Dan Brong, one of the program’s leaders, told the I-Team. “We're seeing more, more horrific calls."

Brong explained after a particularly traumatic or assaultive call, peer counselors check in on firefighters with support and resources to cope with what firefighters face.

In Loudon County, firefighters and dispatchers have new tools to deal with the changes, in part after firefighters were met with a handgun after responding to a call for a possible medical emergency.

Firefighters were dispatched to a supposed cardiac arrest but couldn’t get into the home when they arrived. After minutes of knocking and looking in windows, they had to force entry. When they did, the man, who’d been inside asleep (and not in cardiac arrest), was holding a weapon. Thankfully, no shots were fired.

Now before Loudoun firefighters force their way into a home, they gather more details about who might be inside from neighbors, officers or if there’s been a history of violence at that address.

Loudoun now dispatches calls with important clues for teams responding, describing scenes as hot or cold. A hot scene is code firefighters know. It means be cautious. In some cases, wait for police to join you. It is all aimed to keep firefighters from becoming targets.

“They're very aware of the risk," Loudoun County Fire Battalion Chief Daniel Neal said. "And, you know, everybody wants to go home."

Reported by Ted Oberg, produced by Rick Yarborough, shot by Steve Jones and Jeff Piper, and edited by Steve Jones.

News4 sends breaking news stories by email. Go here to sign up to get breaking news alerts in your inbox.