In 2006, Ebony Magazine declared Prince George's County, Maryland, the wealthiest majority-Black county in America. Some of its richest residents posed for the magazine beside indoor pools and inside their wine cellars.

“When you're here, you realize, oh, this is Black bougie heaven,” says Andre Perry, an expert in race and culture with the Brookings Institute.

As more Black residents packed the suburban enclave east of D.C. along the Potomac River, median income continued to rise. With its golf courses, gated communities, large homes and megachurches, Prince George's County at one point was the second wealthiest county in Maryland, nirvana for its middle- and upper-middle-class Black residents.

“A lot of what motivates Black people is what motivates every American to get a better quality of life,” Perry said. “It's housing, jobs, education. And that's why people move to Prince George's County.”

"People would say, if you come here and then if you leave, you'll understand how special this thing is called Prince George's County," said Dr. Alvin Thorton, a former Howard University professor.

So why are so many of the richest Black Prince George’s residents leaving now? And why are they moving south to Charles County?

Watch the full special report now or read more below.

You can also watch the full documentary on the NBC4 Washington app on Roku or Amazon Fire, or on The Roku Channel, Samsung TV Plus and Xumo Play (just look for NBC Washington D.C. News).

Who's Who

Part 1: Black Picket Fences

Like many Prince Georgians raised in the ‘80s, News4 investigative reporter Tracee Wilkins grew up in the county after her parents moved there from Washington, D.C. Along with her best friend, Wilkins grew up in the Vansville community of Beltsville, a solidly middle-class suburb in the northern part of Prince George’s County.

A generation earlier, their grandparents had migrated to Washington from the Jim Crow south. Wilkins’ maternal grandmother had a federal government job, and her father’s side ran a family business. Both sides of her family bought homes in traditionally Black sections of a then-segregated D.C.

Black people wanted a slice of the American dream just like everyone else.

Andre Perry, Brookings Institute expert in race and culture

Redlining — the racist ways in which housing options were drawn — constrained even those with means from moving out of certain locations, said Chyrl Laird, an associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland College Park.

“So with that, then you have a lot of economic diversity in one community, right?" Laird said. "Because you have upper-middle class Blacks and lower-income Blacks all residing in the same communities together."

Wilkins’ parents met as children at Salem Baptist Church in Northwest D.C., went on to attend Howard University, married and got federal government jobs. When Wilkins’ older sister was born, the family moved from an apartment in Northeast D.C. to a home in Prince George's County.

It was just a few years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, a tragedy that prompted many Black Washingtonians to move out of the District. King’s assassination, and the riots and demonstrations that followed, was a turning point for a lot of cities, Perry said.

"After MLK, MLK's death, you started to see a migration to the suburbs,” Perry said. “Prince George’s being one of the destinations.”

“Black people wanted a slice of the American dream just like everyone else,” he said.

Under pressure to quell the mounting destruction in every part of the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged speedy congressional approval of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

“Black people are wanting to find space; they’re wanting to find community and also dealing with the economic losses and the lack of revitalization, really, to the D.C. region, as a consequence of those riots — which in my opinion, were logical in terms of the fact that people were outraged by what had happened,” Laird said.

Those with means — "we call them Black strivers," Laird said — were able to leave constrained economic conditions or neighborhoods and move into places they found more desirable, she said.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, decennial censuses.

Amy O’Kruk/NBC

Before then, Prince George's County had been essentially a segregated county and a “Southern-leaning, -thinking county," U.S. Rep Steny Hoyer said.

For those moving to Prince George's after the Fair Housing Act was passed, ”fair housing laws were enforced, probably not as well as they should have been, but [they] were enforced,” Hoyer said. His district includes both Prince George’s and Charles counties.

"That decision then to go into Prince George's County, if one had the means and opportunity to do so, was wanting to create, you know, the middle class life that we all see that white families have,” Laird said. “Like, why can't Black people have black picket fences?”

According to U.S. Census data, between 1965 to 1970, more than 62,000 Black people reported leaving the District. From 1975 to 1980, that number jumped to 94,000.

At the same time, the number of Black families moving to Prince George’s County boomed.

It turns out that Wilkins’ parents didn’t just move into a new home in a new county and a new state — they were a part of a migration. So were the parents of her best friend, LaStell.

LaStell's mother, Fannie Minor, remembers when they made the decision move out of the District.

"Well, our children were, number one, going to the schools in D.C. and always coming home upset about a fight here and there," Fannie Minor said. "My husband said, 'This is it. We have to leave out of D.C. We have to check other communities.' So we ventured to Prince George's County."

The two families relocated more than 10 years before Wilkins and her friend were born. Their older sisters experienced something they didn’t, moving from the city to the suburbs. While their neighborhood was majority Black, the county was majority white in the 1970s.

“I was in shock,” recalled LaStell's older sister Vera Howard. “Yeah. It was, like, unreal. They moved us out in the middle of nowhere, no buses. Because in D.C., we had bus transportation. We could go here and there. We could go downtown. We just couldn't believe it... And I was like, 'Where in the world did our parents move us to? To the middle of nowhere.' Yeah, so it was very shocking.”

Vera had attended all-Black schools before starting at Beltsville Junior High School.

“It was a definite culture shock…. And to be in an environment where I was truly a minority,” she said. “I was called the n-word, and I didn't like it. And I hit the guy that said that to me. It was extremely difficult.”

More than two decades earlier, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision Brown vs. the Board of Education had ruled that schools should be desegregated. But it didn’t happen everywhere immediately.

“In ‘72, when Black people were about 12% of the population in Prince George's County, there was massive resistance to the order to desegregate schools,” former Howard University professor Alvin Thorton said.

Thornton fought for decades for equity in education in Prince George’s and the state of Maryland.

“The superintendent, the school board, the political leaders were not willing to do that,” he said. “So the federal court intervened — the federal district court with Judge Kaufman intervened — and said, ‘You're going to desegregate.’”

By the time Tracee Wilkins and LaStell Minor began school in the early 1980s, the county was still majority white, and the girls were bussed to schools out of their community. But as the Black middle and upper middle class were moving in, white people started moving out.

As the two friends got older, it seemed like there were fewer and fewer white residents in the county.

“...I felt like I was in a bubble here in our Black community, so I didn't maybe notice a difference outside of the community. But at our school, it was obvious,” LaStell said.

Part 2: Black Mecca

Note: Dots represent the racial makeup of census block groups and are randomly placed. For this map, racial groups, such as White, Black or Asian, indicate people who identify solely as one race and who are not Hispanic or Latino. Other refers to people who identified as another race or multiple races, and Asian also includes people who identify as Pacific Islanders. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, decennial censuses.

Amy O’Kruk/NBC

In 1994, Prince George’s County elected its first Black county executive, Wayne Curry. Curry was “very smart and not willing to take no” for an answer, Hoyer recalled. “And I think if you were outside of Prince George's County, you saw this dynamic young leader who looked like you. And that was not true of any place else in the suburbs."

Curry would serve two terms leading Prince George’s as it evolved from a majority white blue-collar suburb into one of the most affluent majority-Black jurisdictions in the country. He changed much of the economic landscape, championing construction of FedExField, Bowie Town Center, Wegmans and National Harbor.

I don't have enough words for ‘I'm so proud to be a part of a county like this one.'

Prince George's County Executive Angela Alsobrooks

“Wayne was great because Wayne was, as the image, a University of Maryland law graduate, a professional, a highly charismatic, competent person who had risen up through the ranks of the power structure of Prince George's County,” Thorton said. “So he was you know, he was exactly what you would want.”

As more Black residents moved into the county, income increased, and so did education levels.

"That never happened before in America,” Thorton said. “When Black people come in large numbers, those things normally go down. It did not happen in Prince George's County. And Wayne would always repeat that over and over again, rightfully so, and accurately so, because we were coming.”

By 2010, there were nearly 557,000 Black residents of Prince George’s County, equaling 64.4% of its total population.

"I don't have enough words for ‘I'm so proud to be a part of a county like this one'," current County Executive Angela Alsobrooks said. "I think that Wayne Curry had it exactly right when he talked about the uniqueness of our jurisdiction. It's something that I think deserves to be known across the country. What we produce here, exceptional people, excellent is what it is.”

But at the height of Prince George's prestige, changes in the greater region rippled across the Potomac River.

Note: The annual IRS county-to-county migration estimates are based on tax filing data, which is reflective of approximately 87% of US households. Source: IRS county-to-county migration data, 1990-2019.

Amy O’Kruk/NBC

In the early 2000s, gentrification in Washington, D.C., forced out some of its poorer Black residents who could no longer afford to live in the city. But they could afford the inner Beltway communities in Prince George’s, close to the border with D.C.

We wanted education for our children.... And we were where we could buy homes. And we did that. And then we start saying, 'Well, where's the public facility? .... Where's the hospital? Where's the new school? Where's the whatever?' And there was some frustration associated with that."

Alvin Thorton, former Howard University professor

And, in the county, a unique tax cap made it almost impossible for Prince George's officials to build new schools. Many upper-middle-class and middle-class African Americans who could afford it moved their kids into private schools, essentially abandoning public schools in many parts of the county.

The move had a negative impact on neighborhoods around the schools and the businesses those communities could attract.

Although the county tried to make up for these losses, for some folks, it wasn't enough and it wasn't fast enough.

"We wanted education for our children. I wanted it for my daughters. Your parents wanted it for you," Thornton said. "And we were where we could buy homes. And we did that. And then we start saying, 'Well, where's the public facility? Where the public facilities? .... Where's the hospital? Where's the new school? Where's the whatever?' And there was some frustration associated with that."

The craving for more amenities and better schools followed under the county executives who came after Curry.

Current County Executive Angela Alsobrooks is making some strides building new schools, but she acknowledges there is more to be done.

"I'd be the last person to be disingenuous about that," she said. "We have a lot of successes and some great challenges and generational challenges that we're still working through. And what I've messaged is: If we do that work together, I really don't have any doubt that we can do it. This is a great challenge, not just in Prince George's. It's all across the country, about how we really close up the gap in education between Black and brown children and others."

Part 3: Headed South

In 2005, Black families moving into the Hunter's Brook subdivision in Indian Head, Charles County, watched their stately homes burn.

It wasn’t an accident. It was arson.

The perpetrators caused $10 million in damage, which also included the destruction of 12 unoccupied new homes. Five white men, some volunteer firefighters, were charged in the crimes. One of the suspects who pleaded guilty in federal court said they targeted the homes because "the neighborhood was going Black."

That part was true: In 2000, Black residents accounted for 26.1% of Charles County’s population, a 75% increase from a decade earlier — a major change for this mostly white rural county.

Most of its new residents were coming from Prince George’s County, according to U.S. Census data.

“I mean, because the issue was, ‘Look, we just, we cannot stand the fact that these people are coming in the community and they can afford to purchase these homes’,” Charles County Commission President Reuben Collins said.

Nearly 20 years later, residents and political supporters gathered to celebrate Collins’ latest reelection, and, for the first time, a majority-Black Charles County commission.

It was a clear reflection of what data showed in the latest Census: Prince George’s County continued to provide the biggest flow of people moving to Charles. In 2019, 56% of new people moving to Charles County were coming from Prince George's, according to county-to-county migration data based on IRS tax filers’ changes.

Black families in Charles County also became wealthier, with a rise in median income to more than $106,000, well above the national median of $70,784. The number of families in Charles County earning more than $200,000 tripled during the 2010s, according to a community survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2021, people who identified as Black or mixed with Black made up 54.9% of Charles County population.

Washington Post data reporter Andrew Van Dam was first to report the shift in demographics.

“All of us who follow demographics knew that line was creeping up,” said Washington Post Data Reporter Andrew Van Dam, who was the first to report the shift in demographics. “We knew, that driven by explosive growth in Waldorf, we were seeing an increase in Black population in Charles County, but I don't think any of us quite realized it had actually tipped over and hit the 50% mark, and Black folks are now the majority of the population in Charles.”

Since the income there was already higher, Charles County is now the highest-income majority-Black county in the country, Van Dam said.

Nora Jacques says while she loved growing up in Prince George’s County — "it was just a strong Black community — but when it came time to find a home for her family of seven, she and her husband, Arold, found more house for less money in Charles County.

“The cost of entry to go to P.G. is a little higher than coming into Charles County,” she said. “So you can get a house out here for, you know, $250 [thousand] and it would be a nice-sized home.... But if you're just starting out, in P.G. County, like you would have to be able to purchase a home at $400K. So for us, affordability was definitely a factor.”

So you can get a house out here for, you know, $250[,000] and it would be a nice-sized home.... But if you're just starting out, in P.G. County, you would have to be able to purchase a home at $400K. So for us, affordability was definitely a factor.

Nora Jacques, Charles County homeowner

But after moving to Charles, the Jacques family was disappointed in their neighborhood public school and decided to join the large community of Black parents who homeschool in the county.

“My neighbor, she homeschools, and when we first moved in, that's all she talked about was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I homeschool, you know, this is working for me and my family’,” Nora Jacques said. “So I took her testimony into account. And then there are other families that are always just willing to open up their homes and invite you in and show you how they're doing, what they're doing. So we really found a warm welcome from the homeschooling community.”

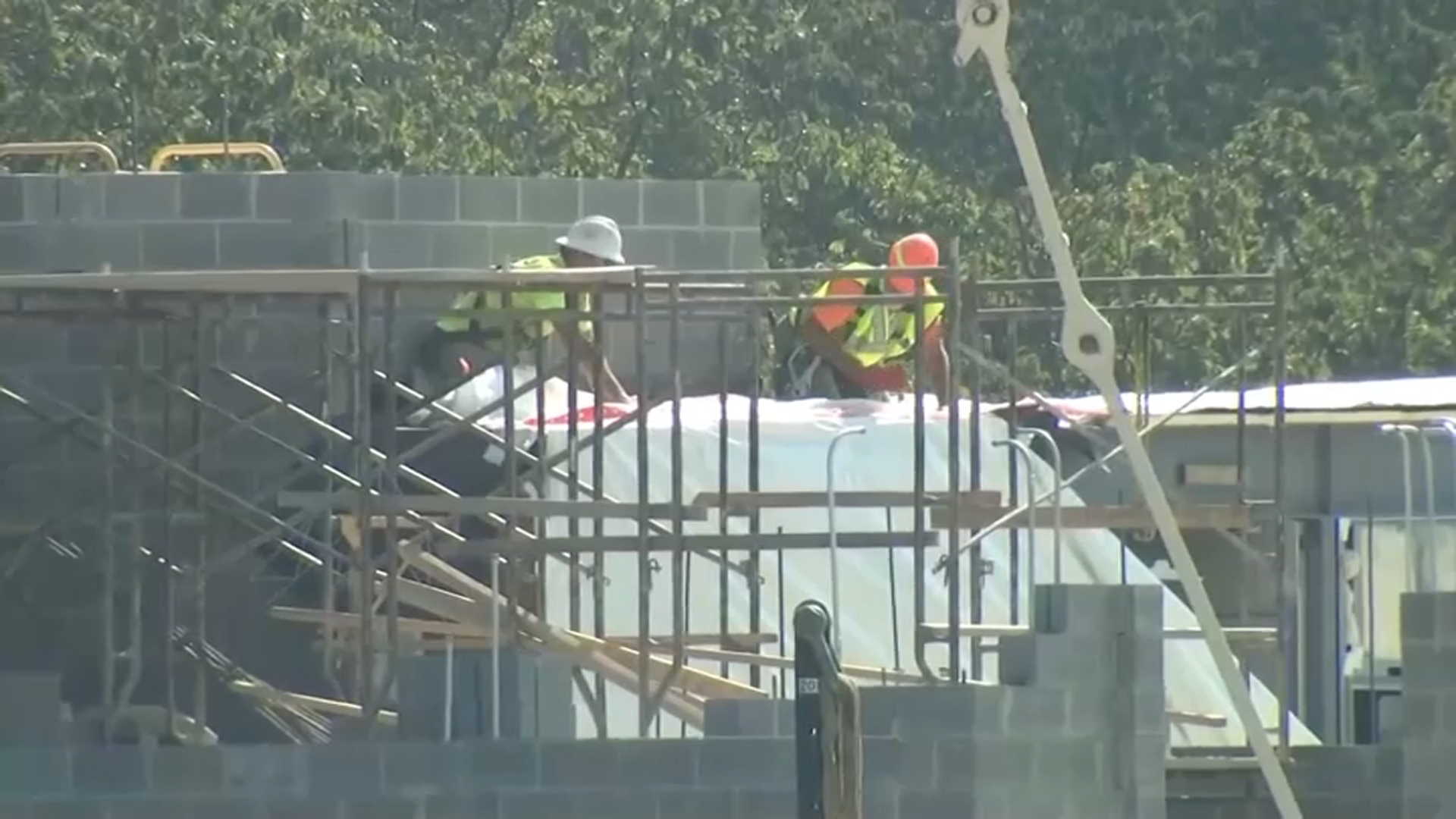

Now the family has another option for schooling. Their son was just accepted into the Phoenix International School of the Arts, the first charter school in Charles County. It was founded by a former resident who moved back and saw the need.

"For far too long, there has not been much school choice here in Charles County," said Angelicka Jackson, co-founder and CEO of the school. "Again, going along with the trend that there's just not enough amenities. There are not a lot of options for families here in Charles County. And while ... our population is growing, particularly African-American families, we found that a lot of these families were leaving the county not just for work, but also searching for educational opportunities outside of the county that would be that would just advance their children's education options and open their options."

The charter school is set to open this fall.

For the Ingram family, the public schools have been the best option. “My kids enjoy school,” said Robbi Ingram, a mom and business owner. “They've succeeded here. We have a good relationship with their teachers. I volunteer.”

Part 4: 'More Opportunities for More People'

When Robbi Ingram and her husband, Syncer, were looking to move from New York to Maryland with their three daughters, they looked at Prince George’s before landing in Charles.

“It was great to see, and to be candid, it was great to see successful people that look like us,” Syncer Ingram said. "I mean, P.G. County had nothing but that everywhere you looked, every profession, everywhere you turned, right? So that really attracted us to that area. And we were looking at homes. We were ready to go.”

But he said the couple heard from many people about recommendations for private schools in Prince George’s.

“So just getting the constant feedback about the schools and the private schools, obviously you read between the lines, you then start picking up maybe the public schools in that area weren't the best,” he said. “So we started doing our comparison solely on schools, and Charles County kept on coming up. Right. So the schools were rated a little bit higher. And that really drove our decision to start looking in this area."

While Charles County's schools are performing only slightly better than Prince George's County schools, based on the latest state assessments released just a few weeks ago, schools are newer in Charles and some may have the perceptions that they are somehow better. News4 found a large number of parents who opted for homeschooling over public schools.

Twice as many parents are homeschooling in Charles as Prince George's county by percentages: 6.4% of Charles County's parents homeschool compared to 3% in Prince George's, according to 2021 Maryland Homeschool Association statistics. However, Prince George's public school system is the second-largest in the state and is four times the size of Charles County's system. So while there are fewer numbers of parents homeschooling, the share is larger.

The real estate listings looked good to the Ingrams, too.

"Once you start looking, you start finding homes similar to what you saw in Bowie, a little bit newer," Syncer Ingram said.

The Ingrams were attracted to the growth that they expected Charles County to see. They now operate Lucianna’s Steakhouse, among other businesses in the county.

“You know, [in] a lot of areas you see growth, but you don't see the infrastructure development to support the growth,” Ingram said. “Fortunately, the commissioner, the you know, the police sheriff, everyone was aligned with the need for growth, but the need to support that growth.”

Charles County Commission President Reuben Collins said they’ve seen a “tremendous” increase in income taxes, which has benefited the county in the long run.

It’s a story of more opportunities for more people, rather than losing opportunities in Prince George's.

Andrew Van Dam, Washington Post data reporter

“And as we move towards the future, we will have to start looking more towards additional amenities for our residents,” Collins said. “And at the top of the list, and this is a regional transportation plan that we've worked on with Prince George's County, and that's Southern Maryland Rapid Transit.”

U.S. Rep. Steny Hoyer also mentioned the challenge of transportation between Charles and Prince George’s, saying there needs to be coordination between the two.

"I think Reuben Collins understands that, you know, Prince George's County and Charles County are essentially in it together," Hoyer said. "And I think [Prince George's County Executive] Angela Alsobrooks also believes that.”

Prince George's County experienced more growth than any county in Maryland according to the 2020 census, but the African American percentage of the population has decreased, and so have some of the higher-income residents this county once boasted.

“It's important to keep in mind that this is not a sign of decline in Prince George’s,” Washington Post data reporter Andrew Van Dam said. "Prince George’s incomes are still rising. Population is still doing well."

Charles County is just growing faster and incomes there are higher, he said.

“It’s a story of more opportunities for more people, rather than losing opportunities in Prince George’s,” Van Dam said.

While some demographics such as wealth have shifted, Prince George’s is still the largest majority African-American county, with the amenities that many upper-middle-class African Americans crave already there or coming soon.

“I don't worry that Prince George's County will lose positioning in any way because others are thriving,” Alsobrooks said. “That's why there is no competition here. People get to choose where they want to live, but I think Prince George's still remains the top choice for people.”

But it's not the only one.

“I'm excited to see that there's more than one place, you know, that Charles County is up and coming,” Robbi Ingram said. “It's the runner-up, it's number one, you know. So I'm excited for more counties to just be as successful as, you know, P.G. County has been and now Charles County.”